Pigeonhole Principle

- Simple form: If $m+1$ pigeons are put into $m$ pigeonholes, then at least one hole contains two or more pigeons

- Another form: If $N$ objects are assigned to $k$ palces, then at least one place must be assigned at least $\lceil N/k\rceil$ objects

- Hint: It’s hard to directly find the “pigeonhole” in practice. A proper division or construction is all you need.

e.g. 1: There are $N=280$ students in this class. What’s the largest value of $n$ that at least $n$ students must have been born in the same month?

\[n=\lceil280/12\rceil=24\]e.g 2: There are several people in the room. Some are acquaintances (symmetric but not reflexive). Show that some two people have the same number of acquaintances.

Assume that there are $n$ people in the room. The possible number of acquaintances ranges from $0$ to $n-1$. If everyone has a different number of acquaintances, then one is bound to have $n-1$ and one $0$ acquaintances. This is a contradition.

e.g 3: Given $m$ integers $a_1,a_2,\dots,a_m$, prove that there exists integers $k$ and $l$ with $0\leq k<l\leq m$ such that $a_{k+1}+a_{k+2}+\dots+a_l$ is divisible by $m$.

Consider that the size of complete residue system modulo $m$ is $m$, so we can just construct $m$ sums $a_1,a_1+a_2,\dots,a_1+a_2+\dots+a_m$. At least one sum have $0$ remainder when divided by $m$.

e.g 4: From the integers $1,2,\dots,200$, we choose $101$ integers. Show that among the integers chosen there are two such that one of them is divisible by the other. (Hint: any integer can be written in the form $2^k\times a$, where $k\geq0$ and $a$ is odd)

Consider that there are $100$ odd numbers in $1$ to $200$. Thus, at least $2$ of these $101$ integers we choose have the same coefficient $a$. One of them is divisible by the other.

- Strong form of Pigeonhole Principle: Let $q_1,q_2,\dots,q_n$ be positive integers. If $q_1+q_2+\dots+q_n-n+1$ objects are put into $n$ boxes, then either 1st box contains at least $q_1$ objects, or the n-th box contains at least $q_n$ objects.

- Let $q_1=q_2=\dots=q_n=r$, then if $n(r-1)+1$ objects are put into $n$ boxes, at least one of the boxes contains $r$ or more the objects.

- Notice that strong form specifies each pigeonhole

e.g 5: A bag contains $100$ apples, $100$ bananas, $100$ oranges and $100$ pears. How many fruits should be taken out such that we can sure a dozen pieces of them are of the same kind?

\[11+11+11+11+1=4\times(12-1)+1=45\]e.g 6: A basket of fruit is being arranged out of apples, bananas, and oranges. What is the smallest number of pieces of fruits that should be put in the basket in order to guarantee that either there are at least $8$ apples or at least $6$ bananas or at least $9$ oranges?

\[7+5+8+1=8+6+9-3+1=21\]e.g 7: There are 100 people at a party. Each people has an even number of acquaintances. Prove that there are three people at the party with the same number of acquaintances. (it is assumed that no one is acquainted with him or herself.)

The possible number of acquaintances are $0,2,4,\dots,98$. There are fifty possibilities. Assuming that there are not three people have the same number of acquaintances, then there is bound to exist two pair that one has $98$ and one $0$ acquaintances. This is a contradition.

e.g. 8: Ramsey, $K_6\rightarrow K_3,K_3$, $K_9\rightarrow K_4,K_4$, turn to the sub-graph.

\[r(2,n)=r(n,2)=n\qquad r(m,n)=r(n,m)\] \[r(3,3)=6\qquad r(3,4)=9\]Assignment 1: Show that if $n+1$ distinct integers are chosen from the set ${1,2,\dots,3n}$, then there are always two which differ by at most $2$.

Assume that the distance between two of these integers is at least $3$, then the ideal situation is $1,4,7,\dots,3n+1$, which conflicts with the question. So there are always two integers which differ by at most $2$.

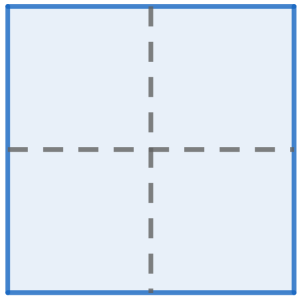

Assignment 2: Prove that of any five points chosen within a square of side length $1$, there are two whose distance apart is at most $\sqrt{2}/2$.

Divide the square into four ares (including all the edges even if overlapped) as figure shows. Obviously any two points in one area whose distance is at most $\sqrt{2}/2$. Throwing five points into four areas means at least $2$ points are in the same area, whose distance apart is at most $\sqrt{2}/2$.

Assignment 3: In a room there are $10$ people with integer ages $[1,60]$. Prove that we can always find two groups of people (with no common person) the sum of whose ages is the same.

Consider the set $P$ of all the ten people, the number of non empty subsets of P is $\vert 2^P-\emptyset\vert=1023$. The possible number of subset sums is $600-10+1=591$, so there must be two subsets of $P$ whose sum is the same. Subtract their common elements separately we can get two groups of people (with no common person) the sum of whose ages is the same.

Permutations and combinations

- Addition and multiplication principle

- Permutation: $P(n,r)=n!/(n-r)!$

- Circular: $P(n,r)/r$, $r$ start points

- Multi-sets: $k^r$, $k$ different types of the element

- Finite repetition numbers: $\displaystyle\frac{n!}{n_1!n_2!\dots n_k!}$, $n=n_1+n_2+\dots+n_k$

- Combination: $C(n,r)=\displaystyle\binom{n}{r}=\frac{n!}{r!(n-r)!}$

e.g. 1: Determine the number of positive integers which are factors of $540$.

\[540=2^2+3^3+5^1\] \[N=3\times4\times2=24\]e.g. 2: How many odd numbers between $1000$ and $9999$ have distinct digits?

\[5\times8\times8\times7=2240\]Hint: All questions about digits and characters combinations are recommended to be done in a placeholder way.

e.g. 3: (Construction Proof) Proof that $C(n,0)+C(n,1)+\dots+C(n,n)=2^n$.

Consider a set $S$ whose size is $n$, the way of collecting its subset is picking $1,2,\dots,n$ elements from $S$, which is the sense of the left side of the equation above. The number of its subset is just $2^n$.

e.g. 4: (Chessboard Problem) There are $n$ rooks of $k$ colors with $n_1$ rooks of the first color, $n_2$ rooks of the second color etc. Determine the number of ways to arrange these rooks on an n-by-n board so that no rook can attack another.

\[n!\times\frac{n!}{n_1!n_2!\dots n_k!}\]e.g. 5: (multiset combination) Let $S$ be a multiset with objects of $n$ different types where each has an infinite repetition number. Determine the number of r-combinations of $S$.

Notice any r-combinations corresponds to an indeterminate equation and vice versa. The number of r-combinations $N$ is equal to the number of solutions of the indeterminate equations as follows:

\[\begin{cases} x_1+x_2+\dots+x_n=r & x_i\in\mathbb{N} \\ y_1+y_2+\dots+y_n=n+r & y_i\in\mathbb{N}^+ \end{cases}\] \[N=\binom{n+r-1}{n-1}=\binom{n+r-1}{r}\]Assignment 1(4-a):

Given the fundamental theorem of arithmetic, each factor can be denoted as $3^i\times5^j\times7^k\times11^l$, where $0\leq i\leq4,0\leq j\leq2,0\leq k\leq6,0\leq l\leq1,i,j,k,l\in\mathbb{N}$, thus:

\[N=5\times3\times7\times2=210\]Assignment 2(7):

Consider the number of put $4$ men in round table firstly, which is $4!/4=3!$. Then put $8$ women into empty places, the number is $8!$, thus:

\[N=3!\times8!=241920\]Assignment 3(19-b):

According to the normal chessboard question, we can first select the coordinates for all the rooks: $C(12,8)\times C(12,8)$. Then determine the number of permutations: $(8!\times8!)/(3!\times5!)$, thus:

\[N=\frac{P(12,8)\times P(12,8)}{3!\times5!}\]Assignment 4(30):

First place $5$ boys in round table: $5!/5=4!$. Then place $5$ girls among the boys: $5!$. At last select the position for parent (It’s important that two boys sit together and this parent sit between them, because if there are two boys sit together, there must exist two girls sit together.), thus:

\[N=4!\times5!\times\binom{10}{1}=28800\]If there are two parents, we have two situations for no boys or girls sit together originally: 1) they sit next to each other, $P(10,2)$; 2) they don’t sit together, $2\times C(10,1)$.

If there are two boys and two girls originally sit together who are divided by a parent, we can say that $BPB$ as a new “boy” and $GPG$ as a new “girl”. The number of these new “boys” or “girls” is $P(5,2)$. So for $4$ boys and girls we can get the number of arrangement is $3!\times4!$, thus:

\[\begin{aligned} N &= 4!\times5!\times(P(10,2)+2\times C(10,1))+3!\times4!\times P(5,2)\times P(5,2) \\ &= 4!\times5!\times(90+20+20) \\ &= 130\times4!\times5!=374400 \end{aligned}\]Assignment 5(61):

The number of all the permutations is $N=9!\times\displaystyle\frac{9!}{5!\times4!}$. Notice if we determine all the coordinates of $n$ rooks of one color, the number of these $n$ rooks permutations is $n!$. So we can first select coordinates for rooks then determine the number of permutations. Denote $N_1$ as first situation and $N_2$ as second situation, then:

\[N_1=\binom{9}{5}\times5!\times\binom{4}{4}\times4!=9!\] \[N_2=5!\times4!\] \[p_1=\frac{N_1}{N}=\frac{5!\times4!}{9!}\qquad p_2=\frac{N_2}{N}=\frac{(5!)^2\times(4!)^2}{9!\times9!}=(\frac{5!\times4!}{9!})^2\]Generating Permutations and Combinations

- mobile integer: its arrow points to a smaller integer adjacent to it

- inversion: the pair $(i_k,i_j)$ is called an inversion if $k<j$ and $i_k>i_j$

- $a_j$: $(x, j)$ which $x$ precedes $j$ while $x>j$ (e.g. $2,3,1$, $a_1=2,a_2=a_3=0$)

Algorithm for generating the permutations of ${1,2,\dots,n}$

- begin with ${\overset{\leftarrow}{1},\overset{\leftarrow}{2},\dots,\overset{\leftarrow}{n}}$

- find the largest mobile integer $m$

- switch $m$ and the adjacent integer its arrow points to

- switch the direction of all integers $p$ with $p>m$

Algorithm for generating permutations from inversion sequence

- Algorithm 1: write down $n$, then put $n-1$ on the left or right of $n$ according to $a_{n-1}$

- Algorithm 2 (recommended): directly determine the position of $1$ according to $a_1$, then iteratively determine $2,3,\dots,n$

Algorithm for generating combinations from $0-1$ sequence $x_{n-1},\dots,x_1,x_0$

- begin with $x_{n-1}\dots x_1x_0=0\dots00$

- find the smallest integer j such that $x_j=0$

- change $x_j,x_{j-1},\dots,x_0$ ($0\rightarrow1$ or $1\rightarrow0$)

Algorithm for generating r-combinations of ${1,2,\dots,n}$ in lexicographic order

- begin with the r-combination $a_1a_2\dots a_r=12\dots r$

- find the largest $k$ such that $a_k<n-r+k$ ($n-r+k$ determines the maximum digit on $a_k$)

- $a_1a_2\dots a_r\rightarrow a_1\dots a_{k-1}(a_k+1)\dots a_k+r-k+1$ (e.g. $n=9,r=5,12389\rightarrow12456$)

theorem 0: The position of r-combinations $a_1a_2\dots a_r$ of ${1,2,\dots,n}$ in the lexicographic ordering is as follows:

\[\binom{n}{r}-\binom{n-a_1}{r}-\binom{n-a_2}{r-1}-\dots-\binom{n-a_r}{1}\]The r-combinations $b_1b_2\dots b_r$ after $a_1a_2\dots a_r$ can be classified into $r$ kinds:

- $b_1>a_1$: there are $C(n-a_1,r)$ such r-combinations

- $b_1=a_1,b_2>a_2$: therer are $C(n-a_2,r-1)$ such r-combinations

- $b_1=a_1,\dots,b_{r-1}=a_{r-1},b_r>a_r$: therer are $C(n-a_r,1)$ such r-combinations

Assignment 1(6-a):

\[a_1=2,a_2=4,a_3=0,a_4=4,a_5=0,a_6=0,a_7=1,a_8=0\]Assignment 2(7-a):

\[\begin{matrix} \_ & \_ & 1 & \_ & \_ & \_ & \_ & \_ \\ \_ & \_ & 1 & \_ & \_ & \_ & 2 & \_ \\ \_ & \_ & 1 & \_ & \_ & \_ & 2 & 3 \\ 4 & \_ & 1 & \_ & \_ & \_ & 2 & 3 \\ 4 & \_ & 1 & \_ & 5 & \_ & 2 & 3 \\ 4 & \_ & 1 & 6 & 5 & \_ & 2 & 3 \\ 4 & \_ & 1 & 6 & 5 & 7 & 2 & 3 \\ 4 & 8 & 1 & 6 & 5 & 7 & 2 & 3 \end{matrix}\]Assignment 3(15-b):

The $0-1$ sequence of ${x_7,x_5,x_3}$ is $10101000$. The smallest $j$ such that $a_j=0$ is $0$. Thus the next sequence is $10101001$, which represents ${x_7,x_5,x_3,x_0}$.

Assignment 4(29):

The largest $k$ which meets $a_k<n-r+k$ is $5$ ($a_5=8$). Thus the next sequence is $1,2,4,6,9,10,11$.

The largest $k$ which meets $a_k-1>0$ and $a_k-1\notin{a_1,\dots,a_7}$ is $6$ ($a_6=14$). Thus the preceding sequence is $1,2,4,6,8,13,15$.

Assignment 5(33):

Consider all the subsets succeed $2489$ in the lexicographic order, then we can get:

\[\text{pos}=\binom{9}{4}-\binom{7}{4}-\binom{5}{3}=81\]Inclusion-Exclusion Principle

Let $P_1,P_2,\dots,P_m$ be $m$ properties referring to the objects in $S$ and let $A_i={x:x\in S,x \text{ has property } P_i}$, then:

\[\vert\bar{A_1}\cap\bar{A_2}\cap\dots\cap\bar{A_m}\vert=\vert S\vert-\sum_{1\leq i\leq m}\vert A_i\vert+\sum_{1\leq i<j\leq m}\vert A_i\cap A_j\vert-\dots+(-1)^m\vert A_1\cap A_2\cap\dots\cap A_m\vert\]Consider any element in $S$ which meets $r$ properties. The following equation demonstrates that right side of above equation count this element just once.

\[1=\binom{r}{1}-\binom{r}{2}+\dots+(-1)^r\binom{r}{r}\]The number of objects of $S$ which have at least one of the properties $P_1,P_2,\dots,P_m$ is given by:

\[\vert A_1\cup A_2\cup\dots\cup A_m\vert=\sum_{1\leq i\leq m}\vert A_i\vert-\sum_{1\leq i<j\leq m}\vert A_i\cap A_j\vert-\dots+(-1)^{m+1}\vert A_1\cap A_2\cap\dots\cap A_m\vert\](r-combinations with finite elements) Let $S$ be a multiset with objects of $k$ different types where each has an finite repetition number. Then the number corresponds to the indeterminate equation as follows:

\[x_1+x_2+\dots+x_k=r\quad x_i\leq c_i\]e.g. 1: Determine the solution number of $x_1+x_2+x_3=10$, which integer $x_i$ meets $0\leq x_1\leq3,0\leq x_2\leq4,0\leq x_3\leq5$.

Denote that $A_1$ meets $x_1>3$, $A_2$ meets $x_2>4$, $A_3$ meets $x_3>5$, $S$ contains all the solutions for $x_1+x_2+x_3=10$ where integer $x_i\geq0$, then:

\[\vert S\vert=\binom{3+10-1}{10}=66\qquad \vert A_1\vert=\binom{3+6-1}{6}=28\] \[\vert A_2\vert=\binom{3+5-1}{5}=21\qquad \vert A_3\vert=\binom{3+4-4}{4}=15\] \[\vert A_1\cap A_2\vert=\binom{3+1-1}{1}=3\qquad \vert A_2\cap A_3\vert=1\] \[\vert A_2\cap A_3\vert=\vert A_1\cap A_2\cap A_3\vert=0\] \[\vert\bar{A_1}\cap\bar{A_2}\cap\bar{A_3}\vert=66-28-21-15+3+1=6\]e.g. 2: (Derangements) A derangement of ${1,2,\dots,n}$ is a permutation $i_1,i_2,\dots,i_n$ such that $i_1\not=1,i_2\not=2,\dots,i_n\not=n$. Determine $D_n$ which is the number of derangements of ${1,2,\dots,n}$.

Denote that $A_i$ represents the number of arrangements where $i$ numbers are in its natural(forbidden) position, thus:

\[\begin{aligned} D_n &= \vert S\vert-\sum_{1\leq i\leq n}\vert A_i\vert+\sum_{1\leq i<j\leq n}\vert A_i\cap A_j\vert-\dots+(-1)^n\vert A_1\cap A_2\cap\dots\cap A_n\vert \\ &= n!-\binom{n}{1}(n-1)!+\binom{n}{2}(n-2)!-\dots+(-1)^n\binom{n}{n} \\ &= n!(1-\frac{1}{1!}+\frac{1}{2!}-\dots+(-1)^n\frac{1}{n!}) \end{aligned}\](Permutations with forbidden positions) Let $X_1,X_2,\dots,X_n$ be subsets of ${1,2,\dots,n}$. We denote by $P(X_1,X_2,\dots,X_n)$ the set of all permutations $i_1i_2\dots i_n$ such that $i_k$ is not in $X_k$. The number of permutations with forbidden positions is defined as follows:

\[p(X_1,X_2,\dots,X_n)=\vert P(X_1,X_2,\dots,X_n)\vert\]In fact, the permutations of $n$ objects correspond to a non-attacking placement of $n$ rooks on a $n\times n$ chessboard. Denote that $r_k$ is the number of ways to place $k$ non-attacking rooks on the n-by-n board where each of the $k$ rooks is in a forbidden position, thus:

\[N=n!-r_1(n-1)!+r_2(n-2)!-\dots+(-1)^nr_n\]Let $r_k(C)$ denote the number of placement of $k$ chesses to the chessboard $C$, thus the chessboard polynomial is defined as follows ($r_0(C)=1$):

\[R(C)=\sum_{k=0}^\infty r_k(C)x^k\]For a specific grid $i$ in $C$, let $C_i$ be a chessboard induced from $C$ by deleting the row and the column of grid $i$. Let $C_e$ be induced from $C$ by deleting grid $i$ from $C$, then we can get several properties:

\[r_k(C)=r_{k-1}(C_i)+r_k(C_e)\] \[R(C)=xR(C_i)+R(C_e)\]If $C$ consists of two independent parts $C_1,C_2$, then we can get $R(C)=R(C_1)R(C_2)$. Thus we can get all the complex $R(C)$ by dividing $C$ into smaller pieces. Some common $R(C)$ is as follows:

Assignment 1(3):

Denote $A_1$ contains all the perfect squares in $[1,10000]$, $A_2$ contains all the perfect cubes in $[1,10000]$. Given that $\lfloor\sqrt{10000}\rfloor=100$, $\lfloor\sqrt[3]{10000}\rfloor=21$, $\lfloor\sqrt[6]{10000}\rfloor=4$, we can get:

\[\vert A_1\vert=100\qquad\vert A_2\vert=21\qquad\vert A_1\cap A_2\vert=4\] \[\begin{aligned} \vert\bar{A_1}\cap\bar{A_2}\vert &= \vert S\vert-\vert A_1\vert-\vert A_2\vert+\vert A_1\cap A_2\vert \\ &= 10000-100-21+4 \\ &= 9883 \end{aligned}\]Assignment 2(8):

Denote that $A_i$ represents all the solutions meeting $x_i>5$, integer $i\in[1,5]$, $S$ contains all the solutions for $x_1+x_2+x_3+x_4+x_5=14$ where integer $x_i\geq1$, thus:

\[\vert S\vert=\binom{14-1}{5-1}=715\qquad\vert A_i\vert=\binom{14-5-1}{5-1}=70\] \[\vert A_i\cap A_j\vert=0,\quad i\not=j\] \[\vert\bigcap_{i=1}^5\bar{A_i}\vert=\vert S\vert-\sum_{i=1}^5\vert A_i\vert= 715-70\times5=365\]Assignment 3(11):

Denote that $A_i$ contains all the permutations meeting that $2i$ is in its natural position, where integer $i\in[1,4]$, $S$ contains all the permutations for ${1,2,\dots,8}$, thus:

\[\begin{aligned} \vert\bigcap_{i=1}^4\bar{A_i}\vert &= \vert S\vert-\sum_{1\leq i\leq 4}\vert A_i\vert+\sum_{1\leq i<j\leq 4}\vert A_i\cap A_j\vert-\dots+(-1)^4\vert A_1\cap A_2\cap\dots\cap A_4\vert \\ &= 8!-\binom{4}{1}7!+\binom{4}{2}6!-\binom{4}{3}5!+\binom{4}{4}4! \end{aligned}\]Assignment 4(25):

Correspond chessboard is as follows:

Assignment 5(31):

Denote that $A_1$ represents all the permutations where all the $a$ appears consecutively. Similar definition also works on $A_2$ to $b$, $A_3$ to $c$, $A_4$ to $d$. To determine $\vert A_i\vert$ easily, we can convert original circular permutation to the linear permutation where all the consecutive letters are fixed at the beginning, (e.g. $aaxxx$, $bbbxxx$) thus:

\[\vert A_1\vert=\frac{12!}{3!\times4!\times5!}\qquad\vert A_2\vert=\frac{11!}{2!\times4!\times5!}\] \[\vert A_3\vert=\frac{10!}{2!\times3!\times5!}\qquad\vert A_4\vert=\frac{9!}{2!\times3!\times4!}\]For two or more sets like $\vert A_1\cap A_2\vert$, we can first convert to linear permutation by fixing consecutive $a$ at the beginning and treat consecutive $b$ as one $b$, thus:

\[\vert A_1\cap A_2\vert=\frac{10!}{1!\times4!\times5!}\qquad\vert A_1\cap A_3\vert=\frac{9!}{3!\times1!\times5!}\] \[\vert A_1\cap A_4\vert=\frac{8!}{3!\times4!\times1!}\qquad\vert A_2\cap A_3\vert=\frac{8!}{2!\times1!\times5!}\] \[\vert A_2\cap A_4\vert=\frac{7!}{2!\times4!\times1!}\qquad\vert A_3\cap A_4\vert=\frac{6!}{2!\times3!\times1!}\] \[\vert A_1\cap A_2\cap A_3\vert=\frac{7!}{1!\times1!\times5!}\quad\vert A_1\cap A_2\cap A_4\vert=\frac{6!}{1!\times4!\times1!}\] \[\vert A_1\cap A_3\cap A_4\vert=\frac{5!}{3!\times1!\times1!}\quad\vert A_2\cap A_3\cap A_4\vert=\frac{4!}{2!\times1!\times1!}\] \[\vert A_1\cap A_2\cap A_3\cap A_4\vert=\frac{3!}{1!\times1!\times1!}\]Define $S$ contains all the circular permutations on given multiset without constraints, hence:

\[\vert S\vert=\frac{14!}{2!\times3!\times4!\times5!\times14}=\frac{13!}{2!\times3!\times4!\times5!}\]Taking all above sets into consideration, we can get $N=\vert\bar{A_1}\cap\bar{A_2}\cap\bar{A_3}\cap\bar{A_4}\vert$ as follows:

\[N=\vert S\vert-\sum_{1\leq i\leq 4}\vert A_i\vert+\sum_{1\leq i<j\leq 4}\vert A_i\cap A_j\vert-\sum_{1\leq i<j<k\leq4}\vert A_i\cap A_j\cap A_k\vert+\vert A_1\cap A_2\cap A_3\cap A_4\vert\]Recurrence Relations and Generating functions

Recurrence Relations

A sequence of numbers $h_0,h_1,\dots,h_n$ is said to satisfy a linear recurrence relation of order $k$, provided there exist quantities $a_1,a_2,\dots,a_k$, with $a_k\not=0$, and a quantity $b_n$ (each of these quantities may depend on $n$) such that:

\[h_n=a_1h_{n-1}+a_2h_{n-2}+\dots+a_kh_{n-k}+b_n,\quad n\geq k\]- homogeneous: when $b_n=0$

- constant coefficients: when $a_1,\dots,a_k$ are constants

Characteristic root method: if the polynomial equation which corresponds to a linear homogeneous recurrence relation $h_n$ has $k$ distinct roots $q_1,q_2,\dots,q_k$, then:

\[h_n=c_1q_1^n+c_2q_2^n+\dots+c_kq_k^n\]Where $c_1,c_2,\dots,c_k$ are undetermined coefficients. If $q_i$ is an s-fold root of the characteristic equation, then its corresponding coefficient is as follows:

\[q_i\rightarrow c_1+c_2n+\dots+c_sn^{s-1}\]e.g. 1: Solve the recurrence relation $h_n=2h_{n-1}+h_{n-2}-2h_{n-3}$ s.t. the initial values $h_0=1,h_1=2,h_2=0$.

Corresponding characteristic equation is as follows:

\[x^3-2x^2-x+2=0\Rightarrow\begin{cases} x_1=1 \\ x_2=-1 \\ x_3=2 \end{cases}\] \[h_n=c_11^n+c_2(-1)^n+c_32^n\] \[\begin{cases} c_1+c_2+c_3=1 \\ c_1-c_2+2c_3=2 \\ c_1+c_2+4c_3=0 \end{cases}\Rightarrow\begin{cases} c_1=2 \\ c_2=-2/3 \\ c_3=-1/3 \end{cases}\]e.g. 2: Words of length $n$, using only the three letters a, b, c are to be transmitted over a communication channel subject to the condition that no word in which two a’s appear consecutively is to be transmitted. Determine the number of words allowed by the communication channel.

Denote $h_n$ as the number of allowed words of length $n$, thus $h_0=1$ and $h_1=3$. Let $n\geq2$. If the first letter of the word is b or c, then the word can be completed in $h_{n-1}$ ways. If the first letter is a, then second letter must be b or c, thus:

\[h_n=2h_{n-1}+2h_{n-2},\quad n\geq2\]e.g. 3: Solve the recurrence relation $h_n=-h_{n-1}+3h_{n-2}+5h_{n-3}+2h_{n-4}$.

\[x^4+x^3-3x^2-5x-2=(x+1)^3(x-2)=0\Rightarrow\begin{cases} x_1=x_2=x_3=-1 \\ x_4=2 \end{cases}\] \[h_n=(c_1+c_2n+c_3n^2)(-1)^n+c_42^n\]Generating functions

In fact, generating function is a special way of counting, whose coefficients correspond to a specific number of possibilities.

\[g(x)=h_0+h_1x+h_2x^2+\dots+h_nx^n+\dots\]e.g. 4: Let $m$ be a positive integer. The generating function for the binomial coefficients is as follows:

\[g(x)=\binom{m}{0}+\binom{m}{1}x+\binom{m}{2}x^2+\dots+\binom{m}{m}x^m=(1+x)^m\]To cope with more complex combination questions, we should give the definition of generalized binomial coefficient:

\[\binom{a}{k}=\begin{cases} a(a-1)\cdots(a-k+1)/k! & k>0 \\ 1 & k=0 \end{cases}\]Give $x,a\in\mathbb{R}$, where $\vert x\vert<1$, then we can do Maclaurin expansion on $(1+x)^a$ to proof it.

\[g(x)=(1+x)^a=\sum_{k=0}^\infty\binom{a}{k}x^k\] \[\begin{aligned} \binom{-n}{k} &= (-n)(-n-1)\cdots(-n-k+1) \\ &= (-1)^kn(n+1)\cdots(n+k-1) \\ &= (-1)^k\binom{n+k-1}{k} \end{aligned}\]e.g. 5: Determine the solution number of $x_1+x_2+x_3=10$ by generating function, which integer $x_i$ meets $0\leq x_1\leq3,0\leq x_2\leq4,0\leq x_3\leq5$.

\[g(x)=(1+x+x^2+x^3)(1+x+x^2+x^3+x^4)(1+x+x^2+x^3+x^4+x^5)\]Absolutely, the solution number of above indeterminate equation is just the coefficient of $x^{10}$, which is $6$.

e.g. 6: Determine the formula of r-combination by generating function.

\[g(x)=(1+x+x^2+\dots)^n=(1-x)^{-n}=\sum_{r=0}^\infty\binom{-n}{r}(-1)^rx^r\] \[N_r=\binom{-n}{r}(-1)^r=\binom{n+r-1}{r}\]e.g. 7: Solve the recurrence relation $h_n=5h_{n-1}-6h_{n-2}$, $n\geq2$ s.t. the initial values $h_0=1$ and $h_1=-2$.

\[g(x)=h_0+h_1x+h_2x^2+\dots+h_nx^n+\dots\] \[(1-5x+6x^2)g(x)=h_0+h_1x-5h_0x=1-7x\] \[g(x)=\frac{1-7x}{1-5x+6x^2}=\frac{5}{1-2x}-\frac{4}{1-3x}=5\sum_{k=0}^\infty(2x)^k-4\sum_{k=0}^\infty(3x)^k\] \[h_n=5\cdot2^n-4\cdot3^n\quad n=0,1,2,\dots\]The exponential generating function for the sequence is defined to be:

\[g^{(e)}(x)=h_0+h_1x+h_2\frac{x^2}{2!}+\dots+h_n\frac{x^n}{n!}+\dots=\sum_{n=0}^\infty h_n\frac{x^n}{n!}\]e.g. 8: Let $n$ be a positive integer. Determine the exponential generating function for the permutations is:

\[\begin{aligned} g^{(e)}(x) &= P(n,0)+P(n,1)x+P(n,2)\frac{x^2}{2!}+\dots+P(n,n)\frac{x^n}{n!} \\ &= \binom{n}{0}+\binom{n}{1}x+\dots+\binom{n}{n}x^n \\ &= (1+x)^n \end{aligned}\]Generally, if $a$ is any real number, the exponential generating function for the sequence $1,a,a^2,\dots a^n,\dots$ is:

\[g^{(e)}(x)=\sum_{n=0}^\infty a^n\frac{x^n}{n!}=e^{ax}\]Let $S$ be the multiset ${n_1\cdot a_1,n_2\cdot a_2,\dots,n_k\cdot a_k}$ where $n_i$ are non-negative integers. Let $h_n$ be the number of n-permutations of $S$. Then the exponential generating function is given by:

\[g^{(e)}(x)=f_{n_1}(x)f_{n_2}(x)\dots f_{n_k}(x)\] \[f_{n_i}(x)=1+x+\frac{x^2}{2!}+\dots+\frac{x^{n_i}}{n_i!}\quad i=1,2,\dots,k\]e.g. 9: Determine the number of ways to color the squares of a 1-by-n chessboard, using the colors red, white, and blue, if an even number of squares are to be colored red.

Let $h_n$ denote the number of such colorings where we define $h_0=1$, thus:

\[\begin{aligned} g^{(e)}(x) &= (1+\frac{x^2}{2!}+\frac{x^4}{4!}+\dots)(1+x+\frac{x^2}{2!}+\dots)(1+x+\frac{x^2}{2!}+\dots) \\ &= \frac{1}{2}(e^x+e^{-x})\cdot e^x\cdot e^x \\ &= \frac{1}{2}(e^{3x}+e^x)=\frac{1}{2}\sum_{n=0}^\infty(3^n+1)\frac{x^n}{n!} \end{aligned}\] \[h_n=\frac{1}{2}(3^n+1)\]e.g. 10: Determine the number $h_n$ of $n$ digit numbers with each digit odd where the digits $1$ and $3$ occur an even number of times.

\[\begin{aligned} g^{(e)}(x) &= (1+\frac{x^2}{2!}+\frac{x^4}{4!}\dots)^2(1+x+\frac{x^2}{2!}+\dots)^3 \\ &= \frac{1}{2}(e^x+e^{-x})\cdot\frac{1}{2}(e^x+e^{-x})\cdot e^x\cdot e^x\cdot e^x \\ &= \frac{1}{4}(e^{5x}+2e^{3x}+e^x) \\ &= \frac{1}{4}\sum_{n=0}^\infty(5^n+2\times3^n+1)\frac{x^n}{n!} \end{aligned}\] \[h_n=\frac{5^n+2\times3^n+1}{4}\]e.g. 11: Determine the number of ways to color the squares of a 1-by-n chessboard, using the colors red, white, and blue, if an even number of squares are to be colored red and there is at least one blue square.

Let $h_n$ denote the number of such colorings, thus:

\[\begin{aligned} g^{(e)}(x) &= (1+x+\frac{x^2}{2!}+\dots)(1+\frac{x^2}{2!}+\frac{x^4}{4!}+\dots)(x+\frac{x^2}{2!}+\frac{x^3}{3!}+\dots) \\ &= \frac{1}{2}(e^{3x}-e^{2x}+e^x-1) \\ &= -\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{2}\sum_{n=0}^\infty(3^n-2^n+1)\frac{x^n}{n!} \end{aligned}\] \[h_0=-\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{2}=0\qquad h_n=\frac{3^n-2^n+1}{2},\quad n=1,2,\dots\]Assignment 1(9):

Let $h_n$ denote the number of such colorings where we define $h_0=1$, $h_1=3$. Assume the first square is white or blue, then the rest squares can be colored in $h_{n-1}$ ways. If the first square is red, then the next square must be white or blue, and the rest squares can be colored in $2h_{n-2}$ ways, thus:

\[h_n=2h_{n-1}+2h_{n-2},\quad n\geq2\] \[x^2-2x-2=0\Rightarrow\begin{cases} x_1=1+\sqrt{3} \\ x_2=1-\sqrt{3} \end{cases}\]We can get $h_n=c_1(1+\sqrt{3})^n+c_2(1-\sqrt{3})^n$ which satisties $h_0$ and $h_1$, hence:

\[\begin{cases} c_1+c_2=1 \\ c_1(1+\sqrt{3})+c_2(1-\sqrt{3})=3 \end{cases}\Rightarrow\begin{cases} c_1=\displaystyle\frac{3+2\sqrt{3}}{6} \\ c_2=\displaystyle\frac{3-2\sqrt{3}}{6} \end{cases}\] \[h_n=\frac{3+2\sqrt{3}}{6}(1+\sqrt{3})^n+\frac{3-2\sqrt{3}}{6}(1-\sqrt{3})^n,\quad n\geq0\]Assignment 2(16):

Determine the number of 4-combinations on the multiset ${2\cdot A,6\cdot B,\infty\cdot C,\infty\cdot D}$ where we need an even number of $B$ and $C$ and at least one $D$.

Assignment 3(25):

\[\begin{aligned} g^{(e)}(x) &= (1+\frac{x^2}{2!}+\frac{x^4}{4!}+\dots)(x+\frac{x^3}{3!}+\frac{x^5}{5!}+\dots)(1+x+\frac{x^2}{2!}+\dots)^2 \\ &= \frac{1}{2}(e^x+e^{-x})\cdot\frac{1}{2}(e^x-e^{-x})\cdot e^{2x} \\ &= \frac{1}{4}(e^{4x}-1)=-\frac{1}{4}+\frac{1}{4}\sum_{n=0}^\infty4^n\frac{x^n}{n!} \end{aligned}\] \[h_n=\begin{cases} 0 & n=0 \\ 4^{n-1} & n\geq1 \end{cases}\]Assignment 4(48-b):

\[g(x)=h_0+h_1x+h_2x^2+\dots+h_nx^n+\dots\] \[(1-x-x^2)g(x)=h_0+h_1x-h_0x=1+2x\] \[g(x)=\frac{1+2x}{1-x-x^2}=\frac{A}{1-\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}x}+\frac{B}{1-\frac{1-\sqrt{5}}{2}x}\] \[\begin{cases} A+B=1 \\ \displaystyle\frac{\sqrt{5}-1}{2}A-\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}B=2 \end{cases}\Rightarrow\begin{cases} A= \displaystyle\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2} \\ B=\displaystyle\frac{1-\sqrt{5}}{2} \end{cases}\] \[g(x)=A\sum_{n=0}^\infty(Ax)^n+B\sum_{n=0}^\infty(Bx)^n=\sum_{n=0}^\infty(A^{n+1}+B^{n+1})x^n\] \[h_n=(\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2})^{n+1}+(\frac{1-\sqrt{5}}{2})^{n+1}\quad n=0,1,2,\dots\]Special Counting Sequences

Catalan numbers

The number of sequences $a_1,a_2,\dots,a_{2n}$ of $2n$ terms that can be formed by using $n\cdot1$ and $n\cdot-1$ whose prefix sums are greater than or equal to $0$.

Denote $A_n$ represents the number of all the legal sequences and $B_n$ all the illegal sequences, thus:

\[A_n=\binom{2n}{n}\]For one illegal sequence, we can find the smallest $k$ such that $a_1+\dots+a_k<0$. Convert $a_1,\dots,a_k$ we can get $B’_n$ consists of $n+1\cdot1$ and $n-1\cdot-1$, obviously $\vert B_n\vert=\vert B’_n\vert$, thus:

\[B_n=\frac{(2n)!}{(n+1)!(n-1)!}\] \[C_n=A_n-B_n=\frac{1}{n+1}\binom{2n}{n}\quad n=0,1,2,\dots\]Difference sequences

The p-order difference sequence is defined as follows. Notice difference has linearity property.

\[\Delta h_n=h_{n+1}-h_n\quad n\geq0\] \[\Delta^ph_n=\Delta(\Delta^{p-1}h_n)\]The general term of the difference sequence can be determined by all the $\Delta^ph_0$ which are on the diagonal position in the difference table.

\[h_n=\Delta^0h_0\binom{n}{0}+\dots+\Delta^ph_0\binom{n}{p}=\sum_{k}\Delta^kh_0\binom{n}{k}\]Denote $\Delta^ph_0$ as $c_p$, we can get any partial sums of a sequence:

\[\sum_{k=0}^n\binom{k}{p}=\binom{n+1}{p+1}\] \[\sum_{k=0}^nh_k=c_0\binom{n+1}{1}+c_1\binom{n+1}{2}+\dots+c_p\binom{n+1}{p+1}\]e.g. 1: Find the sum of the fourth powers of the first $n$ positive integers.

Let $h_n=n^4$, thus diagonal elements in difference table are $0,1,14,36,24,0,0,\dots$, thus:

\[\sum_{k=0}^nk^4=\binom{n+1}{2}+14\binom{n+1}{3}+36\binom{n+1}{4}+24\binom{n+1}{5}\]Stirling numbers

The stirling number of the second kind $S(p,k)$ counts the number of partitions of a set of $p$ elements into $k$ indistinguishable boxes in which no box is empty.

\[S(p,k)=kS(p-1,k)+S(p-1,k-1)\] \[S(p,0)=\begin{cases} 1 & p=0 \\ 0 & p\geq1 \end{cases}\] \[S(p,p)=1\quad p\geq0\]Denote $S^#(p,k)$ counts the number of partitions of a set of $p$ elements into $k$ distinguishable boxes in which no box is empty, thus:

\[S^\#(p,k)=k!S(p,k)\]Denote $A_i$ represents the partition that $i_\text{th}$ box is empty, so $S^#(p,k)=\vert\bigcap_k\bar{A_k}\vert$. Thus:

\[\vert U\vert=k^p\] \[\vert A_{i_1}\cap A_{i_2}\cap\dots\cap A_{i_t}\vert=(k-t)^p\] \[S^\#(p,k)=\sum_{t=0}^k(-1)^t\binom{k}{t}(k-t)^p\]The Bell number $B_p$ is the number of partitions of a set of $p$ elements into non-empty, indistinguishable boxes. Thus:

\[B_p=S(p,0)+S(p,1)+\dots+S(p,p)\]The stirling number $s(p, k)$ of the first kind counts the number of arrangements of $p$ objects into $k$ non-empty circular permutations. Thus:

\[s(p,k)=s(p-1,k-1)+(p-1)s(p-1,k)\] \[s(p,0)=0\quad p\geq1\qquad s(p,p)=1\quad p\geq0\]Partition numbers

A partition of a positive integer n is a representation of n as an unordered sum of one or more positive integers, called parts.

\[4\rightarrow4,1+3,2+2,1+2+1,1+1+1+1\]Let $p_n$ denote the number of different partitions of the positive integer $n$, and for convenience let $p_0=1$. The partition sequence is the sequence of numbers $p_0,p_1,p_2,\dots$ (e.g. $p_4=5$)

$p_n$ equals the number of solutions in nonnegative integers $a_1,a_2,\dots,a_n$ of the equation:

\[na_n+\dots+2a_2+1a_1=n\] \[\begin{aligned} g(x) &= (1+x+x^2+\dots)(1+x^2+x^4+\dots)\dots(1+x^n+x^{2n}+\dots) \\ &= \prod_{k=1}^\infty(1-x^k)^{-1} \end{aligned}\]Assignment 1(1):

Let $h_n$ be the number of ways to draw $n$ lines such that there are no intersections among them. Pick one specific point $A$ and draw a line from this point. This line would have to divide the circle into two regions where should contain an even number of points. (Or we can’t draw $n$ lines meeting the conditions) For each possible line, the regions have $(2k,2(n-k-1))$ points, where $0\leq k\leq n-1$, thus:

\[h_n=\sum_{k=0}^{n-1}h_kh_{n-k-1}=\frac{1}{n}\binom{2n-2}{n-1}\]Assignment 2(7):

\[\Delta^0h_0=1\quad\Delta h_0=-2\quad\Delta^2h_0=6\quad\Delta^3h_0=-3\]Because $h_n$ is a cubic polynomial, $\Delta^kh_0=0$ where integer $k\geq4$. Thus:

\[h_n=\binom{n}{0}-2\binom{n}{1}+6\binom{n}{2}-3\binom{n}{3}\] \[\sum_{k=0}^nh_k=\binom{n+1}{1}-2\binom{n+1}{2}+6\binom{n+1}{3}-3\binom{n+1}{4}\]Assignment 3(25):

$q_n$ equals the number of solutions in nonnegative integers $a_1,a_2,\dots,a_m$ of the equation:

\[a_1t_1+a_2t_2+\dots+a_mt_m=n\]Thus the generation function of $q_0,q_1,\dots,q_n\dots$ is as follows:

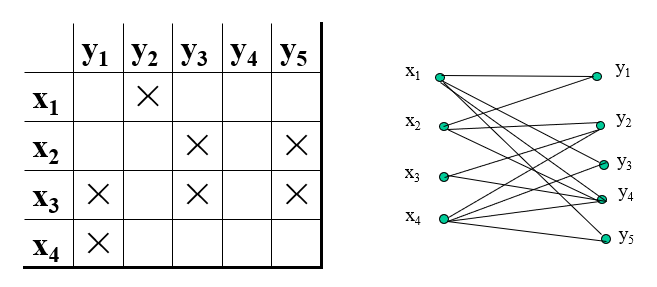

\[\begin{aligned} g(x) &= (1+x^{t_1}+x^{2t_1}+\dots)(1+x^{t_2}+x^{2t_2}+\dots)\dots(1+x^{t_m}+x^{2t_m}+\dots) \\ &= \prod_{k=1}^m(1-x^{t_k})^{-1} \end{aligned}\]Matchings in bipartite graphs

- Independent Set: a set of pairwise nonadjacent vertices in a graph

- Bipartite Graph: A graph consists of two independent sets

- !A cycle in a bipartite graph necessarily has even length

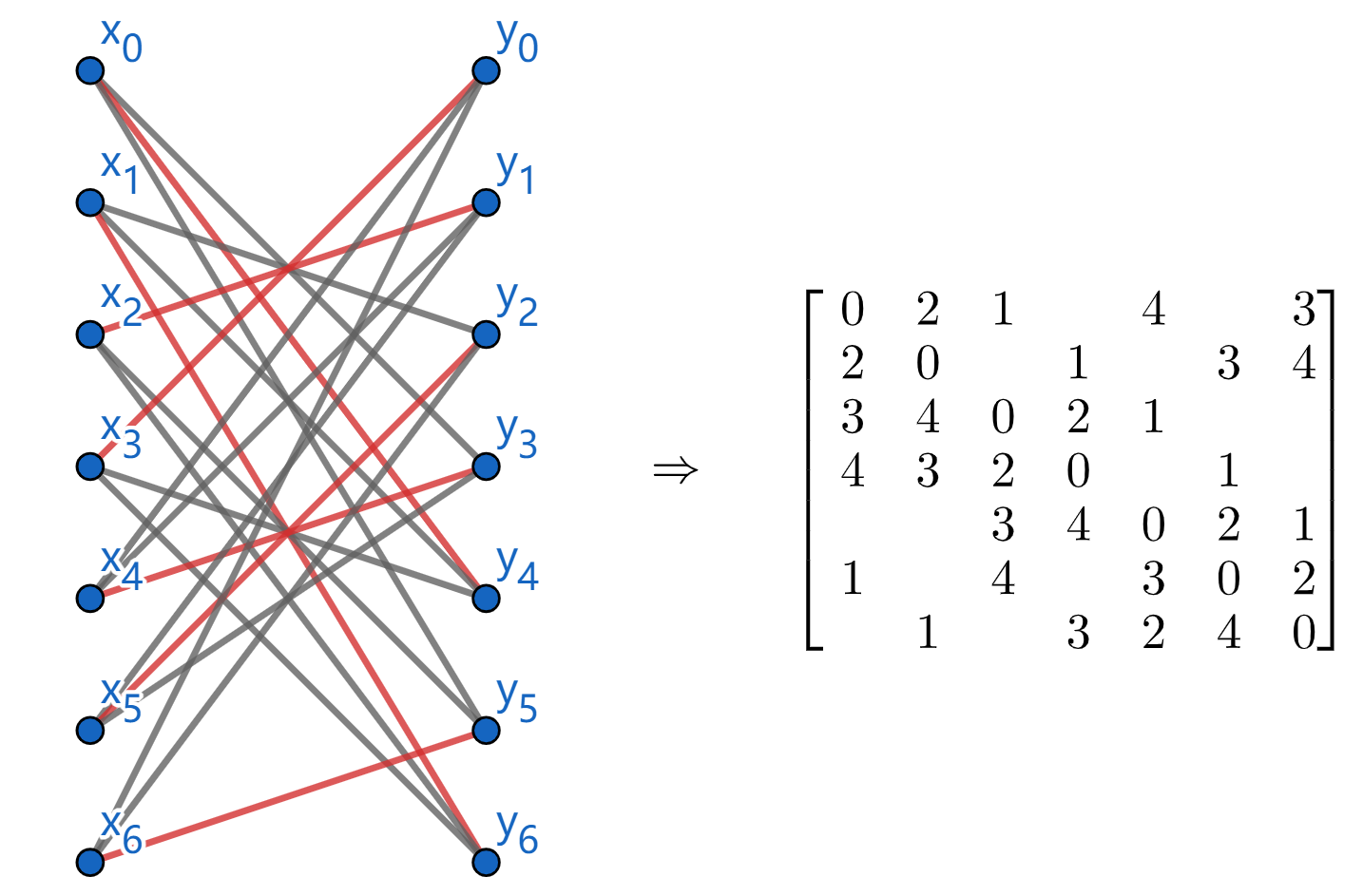

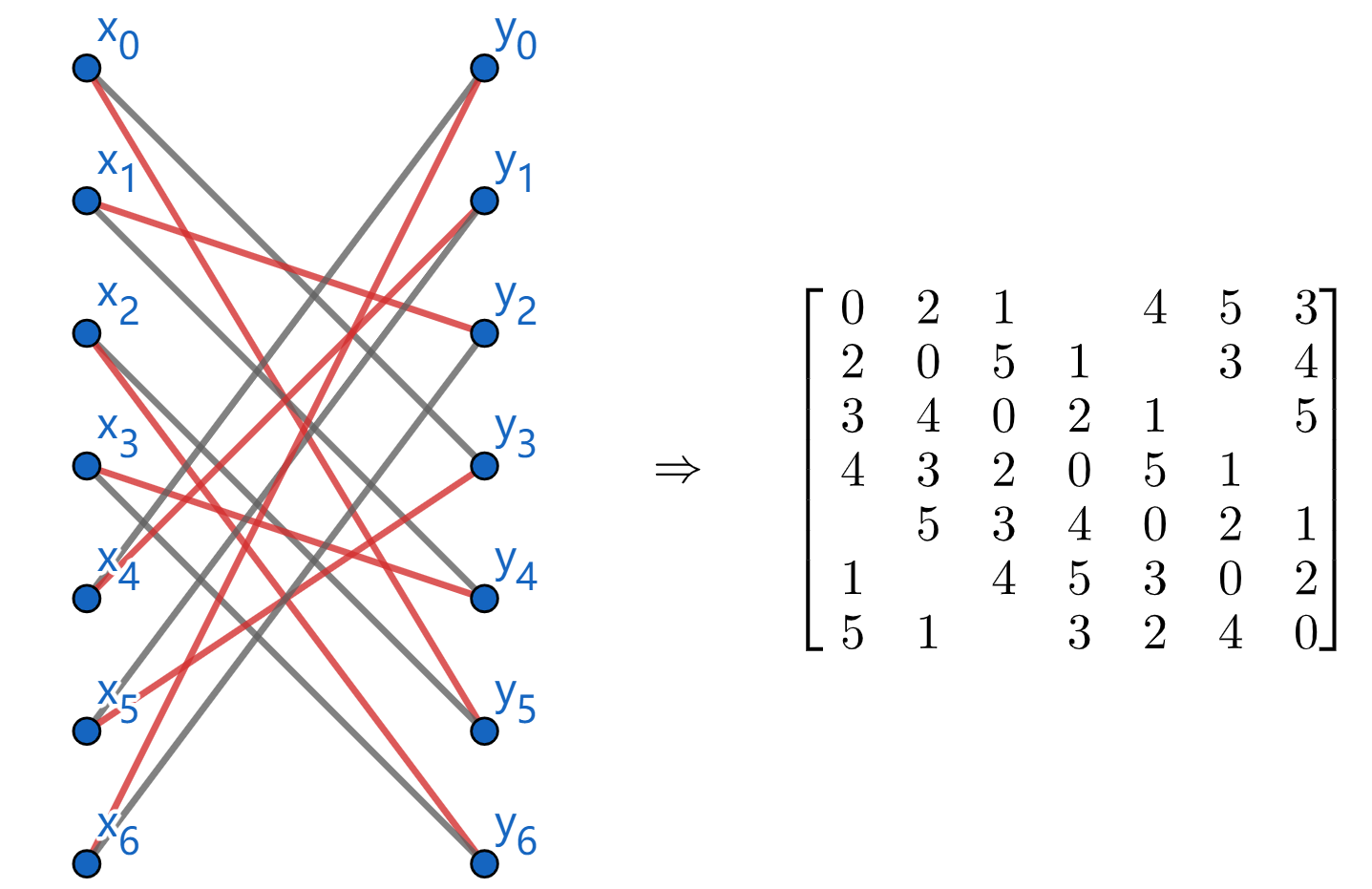

Each bipartite graph is the rook-bipartite graph of some board with forbidden positions when there is no direct path from $x_i$ to $y_j$.

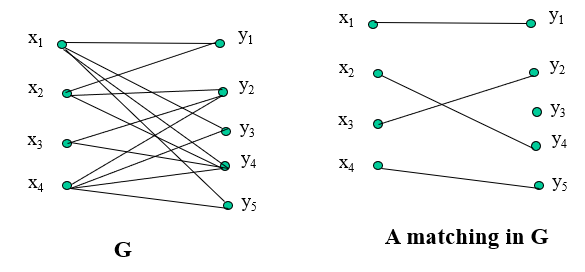

- Matching: A matching in a graph is a set of non-loop edges with no shared endpoints

- Maximal Matching: A maximal matching in a graph is a matching that can not enlarged by adding an edge

- Max-Matching (maximum matching): A max-matching is a matching of maximum size $\rho(G)$ among all matchings in the graph

- M-saturated Vertices: The vertices incident to the edges of a matching

- M-alternating path: Given a matching $M$, and an M-alternating path is a path that alternates between edges in $M$ and edges not in $M$

- M-augmenting path: An M-alternating path whose endpoints are unsaturated by $M$ (convert M-augmenting path so that we can get a larger matching)

- Length: $2k+1$ where $k$ is the size of original matching

- $M_r$: the set of edges of the path that belong to $M$

- $\bar{M_r}$: the set of edges of the path that do not belong to $M$, $\vert\bar{M_r}\vert=\vert M_r\vert+1$

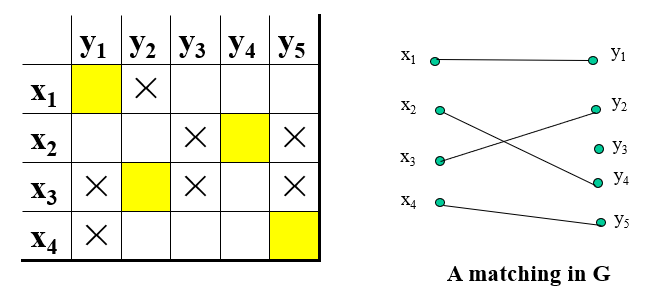

- Vertex Cover: A vertex cover of a graph $G$ is a set $S\subseteq V(G)$ that contains at least one endpoint of every edge

- Min-cover: $c(G)=\vert S\vert$ where the cover $S$ has the smallest number of vertices

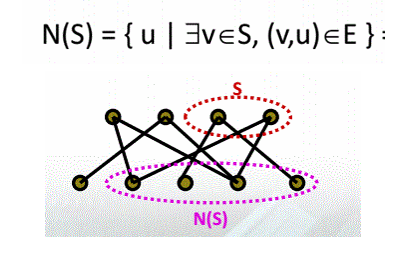

lemma 1: (Hall’s theorem) An X,Y-bigraph $G$ has a matching that saturates $X$ if and only if $\forall S\subseteq X,\vert N(S)\vert\geq\vert S\vert$.

lemma 2: (The Marriage Theorem) A X,Y-bigraph $G$ with $\vert X\vert=\vert Y\vert$ has a perfect matching (all the vertices are saturated) if and only if $\forall S\subseteq X,\vert N(S)\vert\geq\vert S\vert$.

lemma 3: If $G$ is a bigraph, then $\rho(G)\leq c(G)$.

Each vertex of a cover $S$ can incident with at most one edge in a matching $M$, $S$ can “cover” $M$ provided that $\vert S\vert\geq\vert M\vert$.

theorem 1: (Konig theorem) If $G$ is a bipartite graph, then $\rho(G)=c(G)$.

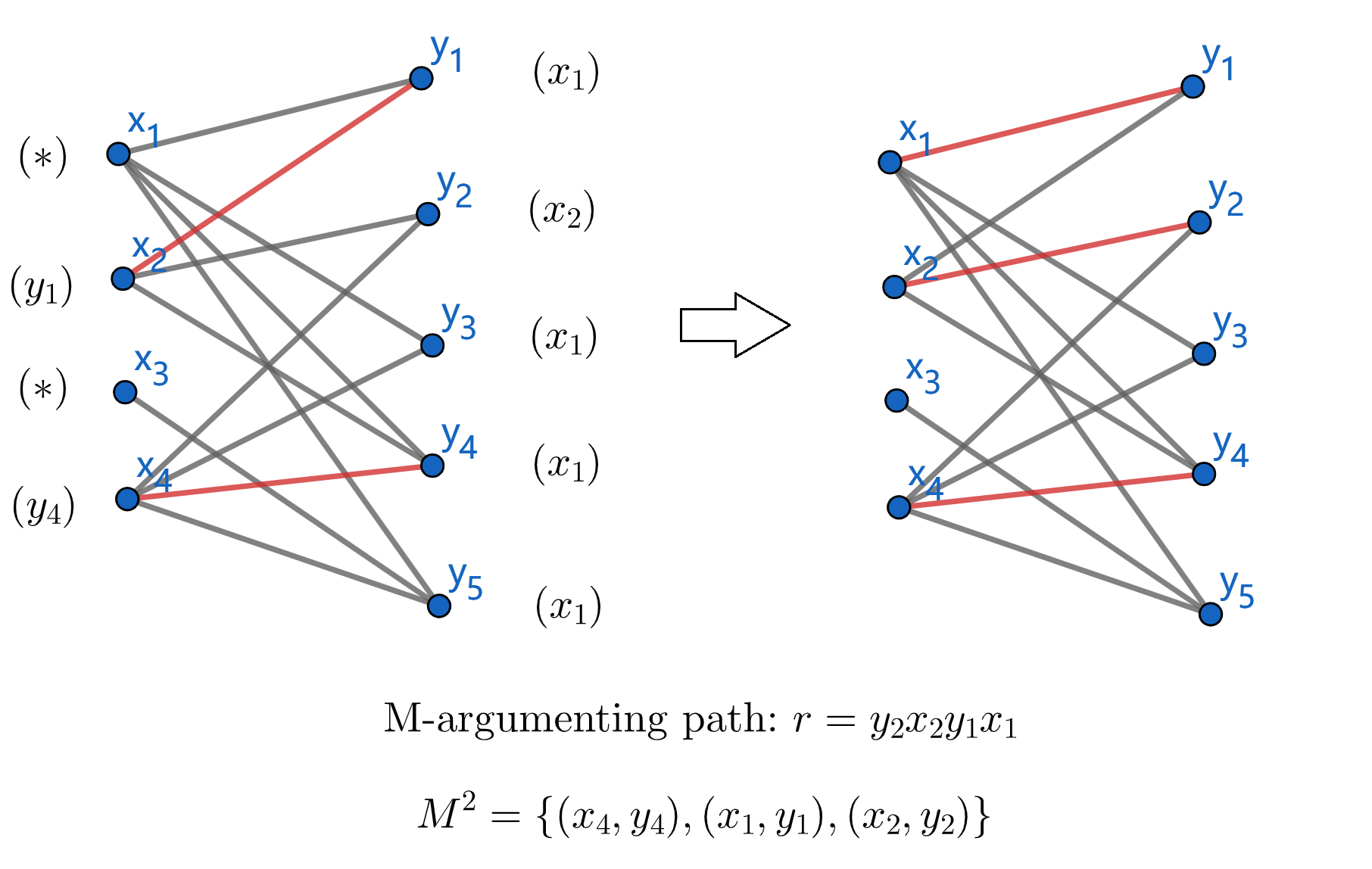

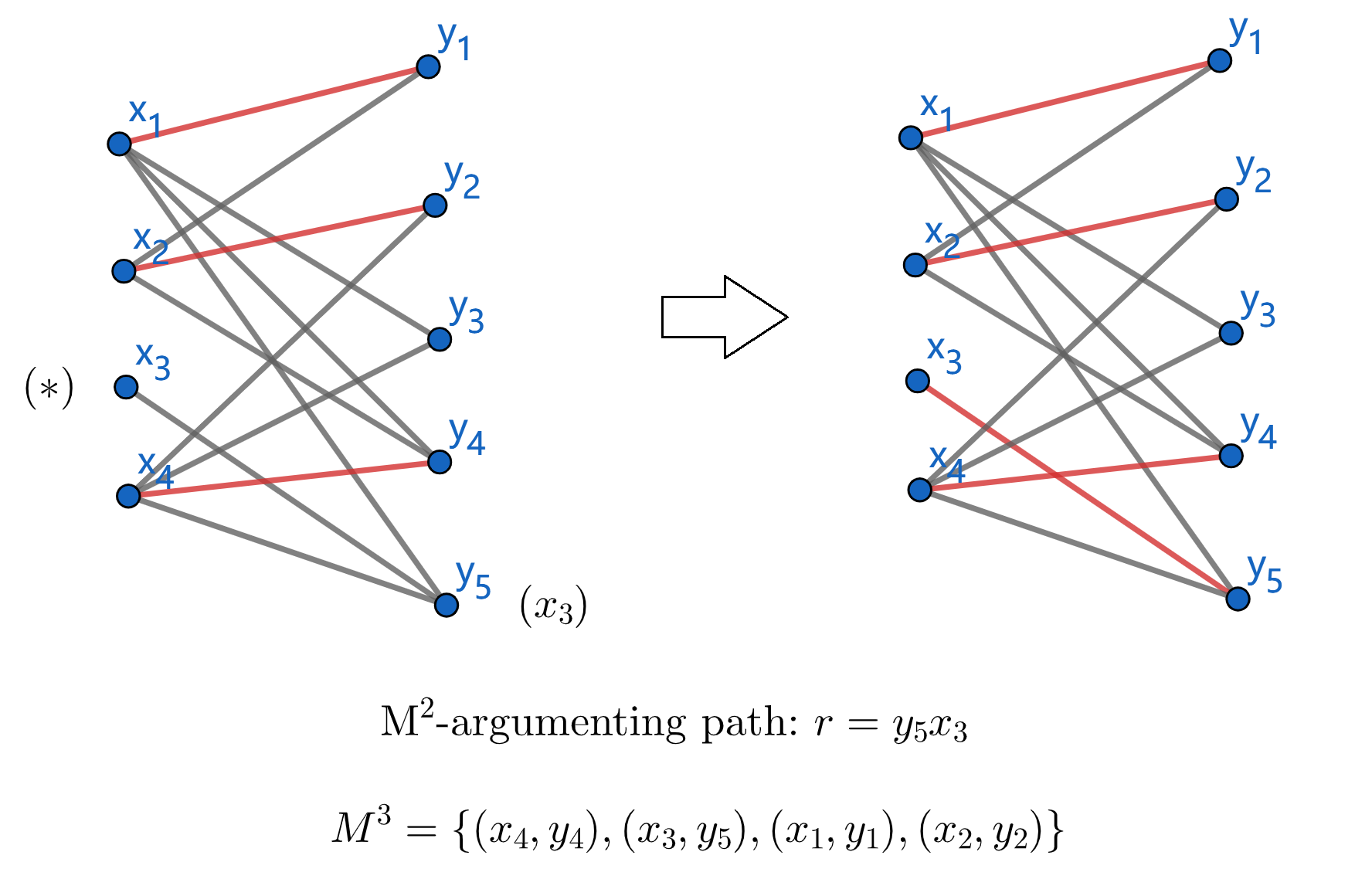

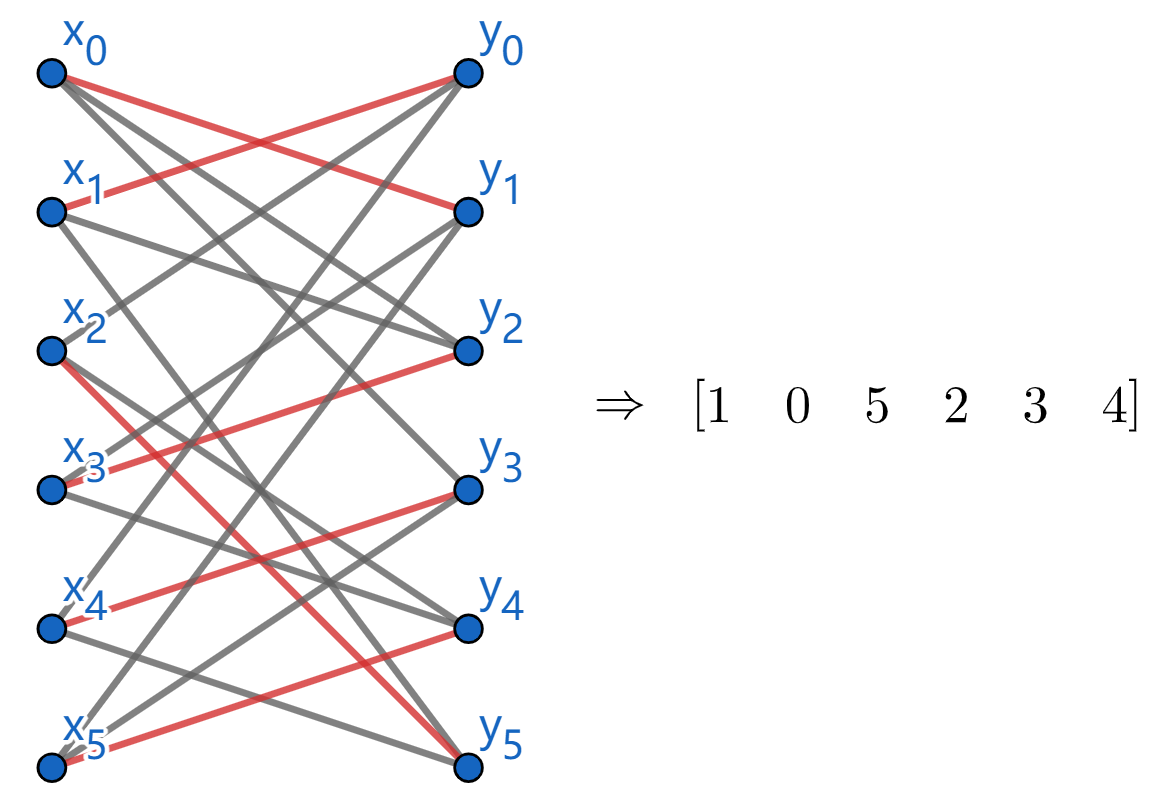

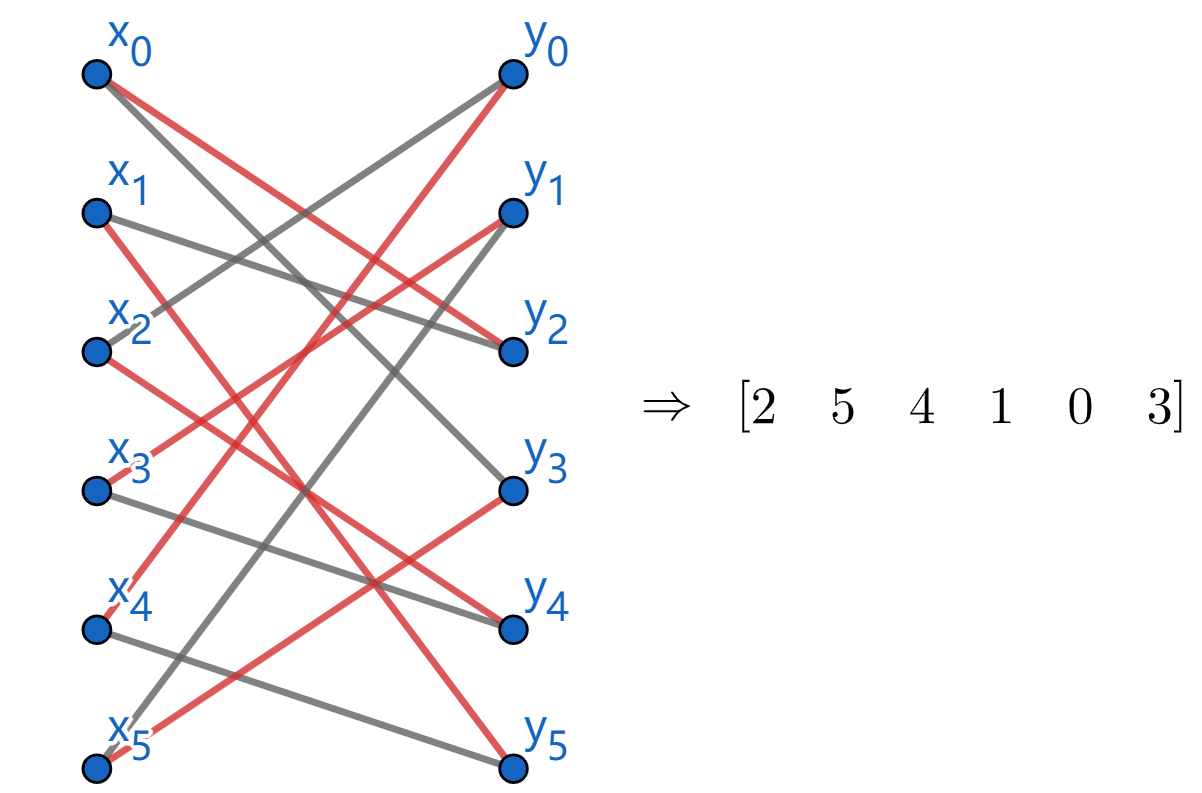

Matching Algorithm: Input an X,Y-bigraph $G$, a matching $M$ in $G$, and the set $U$ of M-unsaturated vertices in $X$. We can get an M-augmenting path or a vertex cover of size $\vert M\vert$ as output.

- Label $*$ for all vertices in $U$ which is unscanned.

- If there is no new label in $X$, stop. Otherwise

goto2. - If there are labelled but unscanned vertices in $X$, label $x_i$ on corresponding vertices $y_j\in Y$ where $e=(x_i,y_j)\notin M$ and $y_j$ has not been labelled. Otherwise

goto3. - If there is no new label in $Y$, stop. Otherwise

goto4. - If there are labelled but unscanned vertices in $Y$, label $y_i$ on corresponding vertices $x_j\in X$ where $e=(x_i,y_j)\in M$ and $x_j$ has not been labelled. Otherwise

goto1.

In the case of breakthrough (there is a labelled vertex of $Y$ which does not meet an edge of $M$ ) occurring in the algorithm, an M-augmenting path can be find. Repeatedly applying matching Algorithm to a bipartite graph will produce a matching and a vertex cover of equal size.

- Matching: Odd M-augmenting path and isolated original matching

- Cover: Labelled vertices in $Y$ and unlabelled vertices in $X$

Extra: Matching in the weighted graphs with KM algorithm.

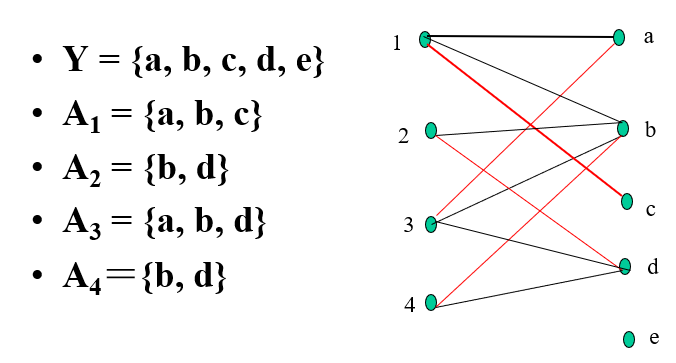

Systems of distinct representatives

Let $Y$ be a finite set and $A={A_1,A_2,\dots,A_n}$ be a series of subsets of $Y$. Denote element $e_i\in A_i$ as the representative of $A_i$. If $e_1,e_2,\dots,e_n$ are different, then they are called a system of distinct representatives. (SDR)

Marriage condition:

\[\forall k\in[1,n],\quad\vert\bigcup_kA_i\vert\geq k\]Denote that $X={1,2,\dots,n}$ represents the index of members in $A$, $Y={y_1,y_2,\dots,y_m}$ and $\Delta={(i,y_j):y_j\in A_i}$. Then we can use $G=(X,\Delta,Y)$ to represent SDR.

$A$ has a SDR if and only if $\rho(G)=n$. The largest number of subsets of $A$ such that they have a SDR equals the smallest value of the following expression:

\[\vert A_{i_1}\cup A_{i_2}\cup\dots\cup A_{i_k}\vert+n-k\quad k=1,2,\dots,n\]Stable marriage

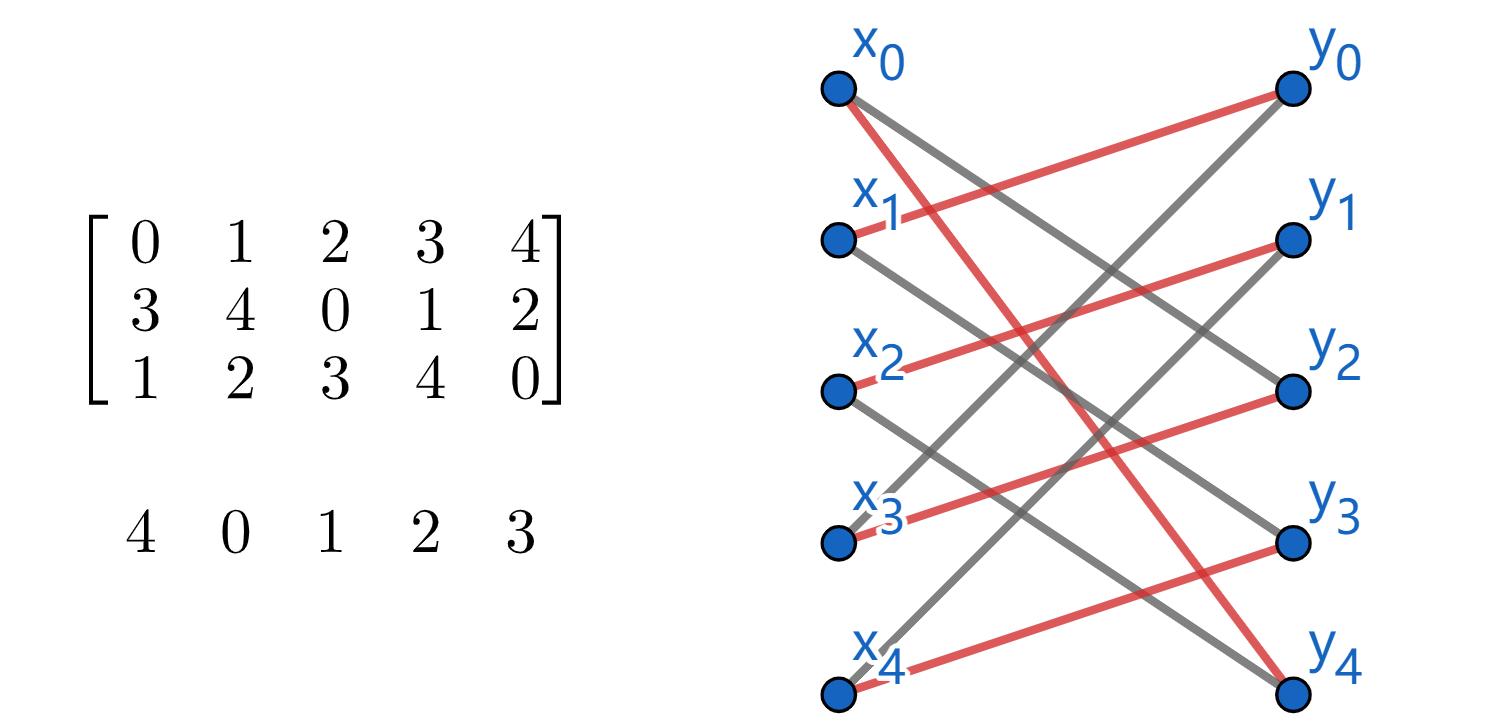

A complete marriage is called unstable, if for two partners, both would regard the partner more preferable than their current spouse. We can define a preferential ranking matrix to depict it.

\[\begin{bmatrix} (1,2) & (2,2) \\ (2,1) & (1,2) \end{bmatrix}\]$(r_1,c_1)=(1,2)$ means $r_1$ put $c_1$ on her first list but $c_1$ put $r_1$ on his second list.

Deferred acceptance algorithm:Each woman first choose her favorite man. Meanwhile, these chosen men should pick the best woman on his list and reject others. Notice it can get women-optimal solution. Switch men and women we can get men-optimal solution.

Assignment 1(7):

\[\vert A_1\cup A_2\cup\dots\cup A_6\vert=5<6\]$A$ does not satisfy the Marriage Condition. Thus, $A$ does not have a SDR. For the largest number of sets of $A$ such that they have a SDR, we have:

\[\min(\vert A_{i_1}\cup A_{i_2}\cup\dots\cup A_{i_k}\vert+n-k)=\begin{cases} 6 & k=1 \\ 6 & k=2 \\ 6 & k=3 \\ 5 & k=4 \\ 5 & k=5 \\ 5 & k=6 \end{cases}\]Thus, the largest number of sets of $A$ which has a SDR is $5$.

Assignment 2(12):

Necessity: Each domino covers two squares with different colors. Thus, the number of allowable white squares and black squares must be the same if the chessboard has a tilling by dominoes.

Sufficiency: Denote that $W={w_1,w_2,\dots,w_n}$ represents all the allowable white squares, $B={b_1,b_2,\dots,b_n}$ represents all the allowable black squares and $S={S_1,S_2,\dots,S_n}$ represents the family of subsets of $B$ which satisfies $b_i\in S_j$ where $b_i$ and $w_j$ are adjacent. If $S$ has a SDR, then the chessboard will have a tilling by dominoes.

Notice that there must be no legal isolated square because we can’t put any domino on it. Thus, we can get $1\leq\vert S_i\vert\leq4$. Then we will proof this proposition through strong mathematical induction.

1) For $t=1$, we have $S={S_1}$ which obviously has a SDR.

2) Assume that $\forall t\in[1,m]$, $S={S_1,S_2,\dots,S_t}$ has a SDR. That is, $\forall k\in[1,t]$, each choice of $k$ different indices $i_1,i_2,\dots,i_k$ satisfies $\vert S_{i_1}\cup S_{i_2}\cup\dots\cup S_{i_k}\vert\geq k$.

3) For $t=m+1$, consider each choice of $k$ different indices $j_1,j_2,\dots,j_k$. Assume that $j_k$ is always the greatest indice, so there are just two conditions that $j_k=m+1$ or $j_k\not=m+1$.

For $j_k\not=m+1$, it is easy to get $\vert S_{j_1}\cup S_{j_2}\cup\dots\cup S_{j_k}\vert\geq k$ due to second step in induction. For $j_k=m+1$, we can get:

\[\vert S_{j_1}\cup\dots\cup S_{j_k-1}\cup S_{m+1}\vert=\vert S_{j_1}\cup\dots\cup S_{j_k-1}\vert+\vert S_{m+1}\vert-\vert(S_{j_1}\cup\dots\cup S_{j_k-1})\cap S_{m+1}\vert\]Denote the set $A$ whose element represents the indice of black square which is adjacent to the $m+1$ white square. If $\forall i\in[1,k]$, $j_i\notin A$, we can get:

\[\vert(S_{j_1}\cup\dots\cup S_{j_k-1})\cap S_{m+1}\vert=0\] \[\vert S_{j_1}\cup\dots\cup S_{j_k-1}\cup S_{m+1}\vert=\vert S_{j_1}\cup\dots\cup S_{j_k-1}\vert+\vert S_{m+1}\vert\geq k-1+1=k\]Else the $m+1$ white square must be adjacent to at least one black square whose indice is in ${j_1,j_2,\dots,j_k}$. Denote the number of these indices is $x$, thus:

\[\vert(S_{j_1}\cup\dots\cup S_{j_k-1})\cap S_{m+1}\vert=x\] \[\vert S_{m+1}\vert\geq x\] \[\vert S_{j_1}\cup\dots\cup S_{j_k-1}\vert\geq k-1+1=k\] \[\vert S_{j_1}\cup\dots\cup S_{j_k-1}\cup S_{m+1}\vert\geq k+x-x=k\]In summary, we proof that for all $t\in[1,n]$, $S$ satisfies marriage condition so that $S$ has a SDR. Thus, the chessboard has a tilling by dominoes.

Assignment 3(19):

Women-optimal:

- $A$ chooses $a$, $B$ chooses $a$, $C$ chooses $b$, $D$ chooses $d$, $a$ rejects $B$

- $B$ chooses $d$, $d$ rejects $D$

- $D$ chooses $b$, $b$ rejects $C$

- $C$ chooses $a$, $a$ rejects $A$

- $A$ chooses $b$, $b$ rejects $A$

- $A$ chooses $c$

The women-optimal stable complete marriage is $Ac,Bd,Ca,Db$.

Men-optimal:

- $a$ chooses $D$, $b$ chooses $B$, $c$ chooses $D$, $d$ chooses $C$, $D$ rejects $a$

- $a$ chooses $C$, $C$ rejects $d$

- $d$ chooses $B$, $B$ rejects $b$

- $b$ chooses $D$, $D$ rejects $c$

- $c$ chooses $A$

The men-optimal stable complete marriage is $Ac,Bd,Ca,Db$, same to women-optimal solution. Thus, there is only one stable complete marriage.

Assignment 4(extra):

Apply matching algorithm to $M^3$, we can not find any breakthrough point. Thus, $M^3={(x_3,y_5),(x_4,y_4),(x_1,y_1),(x_2,y_2)}$ is the max-matching. The min-cover is ${y_5,x_1,x_2,x_4}$.

Notice that $y_3$ is the only vertex uncovered by max-matching. Add $(x_1,y_3)$ to max-matching so that we can get the minimun edge cover ${(x_3,y_5),(x_4,y_4),(x_1,y_1),(x_2,y_2),(x_1,y_3)}$.

Combinatorial Designs

Modular arithmetic

- $\mathbb{Z}_n={0,1,2,\dots,n-1}$

- $a\oplus b=(a+b)\bmod n$

- $a\otimes b=(a\times b)\bmod n$

- Additive inverse ($-a$): integer $b$ such that $a\oplus b=0$

- Multiplication inverse ($a^{-1}$): integer $b$ such that $a\otimes b=1$

- $\gcd(a,b)=\gcd(b,a\bmod b)$

According to Bezout theorem $\gcd(a,b)=1\Rightarrow\exists x,y\in\mathbb{Z},ax+by=1$, we can compute inverse of $m$ in $\mathbb{Z}_n$ by exgcd. Consider gcd(47,30)=1, we can get that $30^{-1}=11$.

Field

For each prime $p$ and each integer $k\geq2$, we can add $i$ to construct a field with $p^k$ elements. Notice that $i$ has the same property with $1$ in $\mathbb{Z}$. For example $\mathbb{Z}_2$ and $x^3+x+1$, we can construct a field ${a+bi+c^2:a,b,c\in\mathbb{Z}_2}$.

\[i^3=-i-1=i+1\] \[(1+i)+(1+i+i^2)=i^2\] \[i^2\times(1+i+i^2)=1\]For $(1+i)^{-1}$, we can assume that it is $a+bi+ci^2$ to solve it.

Block designs

- $k,\lambda,v$: positive integers with $2\leq k\leq v$

- $X$: a set of $v$ elements (varieties)

- $B$: a collection $B_1,B_2,\dots,B_b$ which is $k$ element subsets of $X$, called blocks

- $r$: the number of blocks containing each variety

- $\lambda$: each pair of elements of $X$ occurs in exactly $\lambda$ blocks, called index of the (balanced) design

- $(k-1)r=(v-1)\lambda$, $bk=vr$

- SBIBD: $b=v$

If $k<v$ and $B$ is balanced, then we have a balanced incomplete block design (BIBD). We can use an incidence matrix to depict it.

\[a_{ij}=\begin{cases} 1 & x_j\in B_i \\ 0 & x_j\notin B_i \end{cases}\]e.g. 1: Construct a BIBD with parameters $b=v=7$, $k=r=3$, $\lambda=1$.

\[B_1=\{0,1,3\}\quad B_2=\{1,2,4\}\quad B_3=\{2,3,5\}\quad B_4=\{3,4,6\}\] \[B_5=\{4,5,0\}\quad B_6=\{5,6,1\}\quad B_7=\{6,0,2\}\]Notice that a complementary design to one SBIBD is also a SBIBD. In the above example, we construct a SBIBD with $\oplus$. ($B_2=B_1\oplus1$) In fact if we start with ${0,1,4}$, we can’t get a BIBD. Let $B$ be a subset of $k$ integers in $\mathbb{Z}_v$. If each non-zero integer in $\mathbb{Z}_v$ occurs the same times $\lambda$ in $k(k-1)$ differences ${x-y:x,y\in B,x\not=y}$, then $B$ can be called a difference set $\bmod v$. Thus:

\[\lambda=\frac{k(k-1)}{v-1}\] \[\begin{matrix} - & 0 & 1 & 3 \\ 0 & 0 & 6 & 4 \\ 1 & 1 & 0 & 5 \\ 3 & 3 & 2 & 0 \end{matrix}\]Start with ${0,1,3}$, then we can construct a BIBD because $B$ is a difference set $\bmod7$.

Steiner triple systems

A BIBD is called steiner triple systems when $k=3$. According to general properties of BIBD we can get:

\[r=\frac{\lambda(v-1)}{k-1}=\frac{\lambda(v-1)}{2}\] \[b=\frac{vr}{k}=\frac{\lambda v(v-1)}{6}\]Assume that $\lambda=1$, then $v$ must be $6n+1$ or $6n+3$ where $n$ is a nonnegative integer.

theorem 1: If there are two steiner triple systems with $v$ and $w$ varieties, then we can construct one steiner triple systems with $vw$ varieties.

Assume that $B_v$ has varieties $a_1,a_2,\dots,a_v$ and $B_w$ has varieties $b_1,b_2,\dots,b_w$. We can construct $B_{vw}={c_{il},c_{js},c_{kt}}$ by the following matrix:

\[\begin{matrix} & \begin{matrix} b_1 & b_2 & \cdots & b_w \end{matrix} \\ \begin{matrix} a_1 \\ a_2 \\ \vdots \\ a_v \end{matrix} & \begin{bmatrix} c_{11} & c_{12} & \cdots & c_{1w} \\ c_{21} & c_{22} & \cdots & c_{2w} \\ \vdots & \cdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ c_{v1} & c_{v2} & \cdots & c_{vw} \end{bmatrix} \end{matrix}\]- $i=j=k$ when ${b_i,b_j,b_k}\in B_w$

- $l=s=t$ when ${a_l,a_s,a_t}\in B_v$

- $i\not=j\not=k$ and $l\not=s\not=k$ when ${b_i,b_j,b_k}\in B_w$ and ${a_l,a_s,a_t}\in B_v$

e.g. 2; Determine the size of $B_{21}$ construsted from $B_3$ and $B_7$.

\[N=7+3\times7+3!\times7=70\]If the triples of B can be partitioned into parts so that each variety occurs in exactly one triple in each part, then the Steiner triple system is called resolvable and each part is called a resolvability class.

Notice that if a steiner triple systems is resolvable, $v$ must be $6n+3$ in order that $v\mid3$.

Latin Squares

A latin square of order $n$ is a n-by-n array where each of $n$ elements occurs exactly once in each row and column. We denote that $A(k)$ represents the set of positions occupied by $k$.

\[a_{ij}=i+j(\bmod3)\Rightarrow\begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 & 2 \\ 1 & 2 & 0 \\ 2 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}\]Consider $R_n$ and $S_n$ as follows. We can apply $R_n\times A$ or $S_n\times A$ to examine if $A$ is a latin square. (If so, each of the ordered pairs in $\mathbb{Z}_n$ occurs exactly once in compound matrix)

\[R_n=\begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \\ 1 & 1 & \cdots & 1 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \cdots & \vdots \\ n-1 & n-1 & \cdots & n-1 \end{bmatrix}\qquad S_n=\begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 & \cdots & n-1 \\ 0 & 1 & \cdots & n-1 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \cdots & \vdots \\ 0 & 1 & \cdots & n-1 \end{bmatrix}\] \[R_3\times\begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 & 2 \\ 1 & 2 & 0 \\ 2 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix} (0,0) & (0,1) & (0,2) \\ (1,1) & (1,2) & (1,0) \\ (2,2) & (2,0) & (2,1) \end{bmatrix}\]Let $A$ and $B$ be lain squares in $\mathbb{Z}_n$. If each of the ordered pairs in $\mathbb{Z}_n$ occurs exactly once in $A\times B$, we call that $A$ and $B$ are orthogonal. We refer to mutually orthogonal Latin squares as MOLS.

Let $n$ be a positive integer and $r$ be a non-zero integer in $\mathbb{Z}n$ such that $\gcd(r,n)=1$. Then we can construct a latin square $L_n^r$ by $a{ij}=r\times i+j(\bmod n)$. If $n$ is a prime number, then $L_n^1,L_n^2,\dots,L_n^{n-1}$ are $n-1$ MOLS.

If $n$ is not a prime number, we can construct latin squares by field. Let $a_0=0,a_1,\dots,a_{n-1}$ be the elements of field $F$, then $a_{ij}=a_r\times a_i+a_j(r\not=0)$. If $n=p^k$ where $p$ is a prime number, then $L_n^{a_1},L_n^{a_2},\dots,L_n^{a_{n-1}}$ are $n-1$ MOLS.

- The largest number $N(n)$ of MOLS of order $n$ is at most $n-1$

- $N(n)\geq2$ for each odd integer $n$

- $N(nm)\geq\min(N(n),N(m))$

- $n=p_1^{e_1}\times\dots\times p_k^{e_k}\Rightarrow N(n)\geq\min(p_i^{e_i}-1:i=1,2,\dots,k)$

For two small MOLS $A_1,A_2$ and $B_1,B_2$, we can apply $a_{ij}\times B$ to generate ordered pair which can be converted into integer to construct larger MOLS. (e.g. for MOLS of order $3$ and $4$, $(2,3)=11$)

MOLS and BIBD

If there exist $n-1$ MOLS of order $n$, then there exists a resolvable BIBD with parameters:

\[b=n^n+n\quad v=n^2\quad k=n\quad r=n+1\quad\lambda=1\]Let $A_1,A_2,\dots,A_{n-1}$ be $n-1$ MOLS of order $n$, then we can generate $n(n+1)$ blocks which has $n$ elements by the following square:

\[\begin{matrix} R_n(0) & R_n(1) & \cdots & R_n(n-1) \\ S_n(0) & S_n(1) & \cdots & S_n(n-1) \\ A_1(0) & A_1(1) & \cdots & A_1(n-1) \\ \vdots & \vdots & \cdots & \vdots \\ A_n(0) & A_n{1} & \cdots & A_n(n-1) \end{matrix}\]For example, $n=3$, $R_3(0)={(0,0),(0,1),(0,2)}\rightarrow{0,1,2}$. Each ordered pair corresponding to position can be converted into integer so that we can construct a BIBD from MOLS.

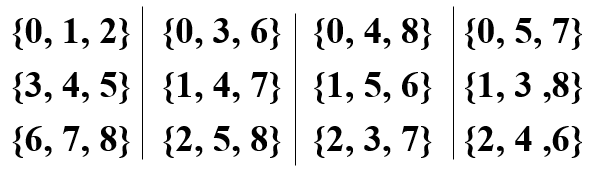

e.g. 3: Suppose $9$ varieties of products need to be tested by $12$ consumers. Each consumer is asked to compare a certain $3$ of the varieties. The test is to have a property that each pair of the $9$ varieties is compared by exactly one person and each one variety is tested by $4$ consumers. How to design the blocks?

Since $3$ is a prime number, we can get that $a_{ij}=r\times i+j(\bmod3)$. Thus:

\[L_3^1=\begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 & 2 \\ 1 & 2 & 0 \\ 2 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}\quad L_3^2=\begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 & 2 \\ 2 & 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 2 & 0 \end{bmatrix}\]The following square determines the blocks we need.

\[\begin{matrix} R_3(0) & R_3(1) & R_3(2) \\ S_3(0) & S_3(1) & S_3(2) \\ L_3^1(0) & L_3^1(1) & L_3^1(2) \\ L_3^2(0) & L_3^2(1) & L_3^2(2) \end{matrix}\] \[B_1=\{0,1,2\}\quad B_2=\{3,4,5\}\quad B_3=\{6,7,8\}\quad B_4=\{0,3,6\}\] \[B_5=\{1,4,7\}\quad B_6=\{2,5,8\}\quad B_7=\{0,5,7\}\quad B_8=\{1,3,8\}\] \[B_9=\{2,4,6\}\quad B_{10}=\{0,4,8\}\quad B_{11}=\{1,5,6\}\quad B_{12}=\{2,3,7\}\]e.g. 4: Suppose $16$ varieties of products need to be tested by $20$ consumers. Each consumer is asked to compare a certain $4$ of the varieties. The test is to have a property that each pair of the $16$ varieties is compared by exactly one person and each one variety is tested by $5$ consumers. How to design the blocks?

Consider the 4-element field ${a_0=0,a_1=1,a_2=i,a_3=1+i}$. We obtain the following Latin squares: (remind of that $i^2=i+1$, $a_{ij}=a_r\times a_i + a_j$)

\[L_4^1=\begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 & i & 1+i \\ 1 & 0 & 1+i & i \\ i & 1+i & 0 & 1 \\ 1+i & i & 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix}\quad L_4^i=\begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 & i & 1+i \\ i & 1+i & 0 & 1 \\ 1+i & i & 1 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 1+i & i \end{bmatrix}\quad L_4^{1+i}=\begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 & i & 1+i \\ 1+i & i & 1 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 1+i & i \\ i & 1+i & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}\]Replace $i$ by $2$ and $1+i$ by $3$. Then we can construct blocks we need from $R_4,S_4,L_4^1,L_4^2,L_4^3$ just like $n=3$.

Incomplete Latin square

In fact, we can arbitrarily switch the position of two numbers in Latin square (e.g. switch $1$ and $2$). Thus, we can directly put an allowable number into incomplete Latin square just like sudoku.

Assignment 1(16):

\[\begin{matrix} 46=15\times3+1 & 1=46\times1+15\times(-3) \end{matrix}\]Thus, the multiplication inverse of $15$ in $\mathbb{Z}_{46}$ is $-3\bmod46=43$.

Assignment 2(21):

The BIBD with parameters $b=v=7,k=r=3,\lambda=1$ is:

\[B_1=\{0,1,3\}\quad B_2=\{1,2,4\}\quad B_3=\{2,3,5\}\quad B_4=\{3,4,6\}\] \[B_5=\{4,5,0\}\quad B_6=\{5,6,1\}\quad B_7=\{6,0,2\}\]Thus, the complementary design of this BIBD is as follows:

\[\bar{B_1}=\{2,4,5,6\}\quad\bar{B_2}=\{0,3,5,6\}\quad\bar{B_3}=\{0,1,4,6\}\quad\bar{B_4}=\{0,1,2,5\}\] \[\bar{B_5}=\{1,2,3,6\}\quad\bar{B_6}=\{0,2,3,4\}\quad\bar{B_7}=\{1,3,4,5\}\]Assignment 3(28):

\[\begin{matrix} \text{-} & 0 & 1 & 3 & 9 \\ 0 & 0 & 12 & 10 & 4 \\ 1 & 1 & 0 & 11 & 5 \\ 3 & 3 & 2 & 0 & 7 \\ 9 & 9 & 8 & 6 & 0 \end{matrix}\]Each non-zero integer in $\mathbb{Z}_{13}$ occurs once in difference table, so $B$ is a difference set $\bmod13$. The parameters of this SBIBD is as follows;

\[b=v=13\quad k=r=4\quad\lambda=\frac{k(k-1)}{v-1}=1\] \[B+0=\{0,1,3,9\}\quad B+1=\{1,2,4,10\}\quad B+2=\{2,3,5,11\}\] \[B+3=\{3,4,6,12\}\quad B+4=\{0,4,5,7\}\quad B+5=\{1,5,6,8\}\] \[B+6=\{2,6,7,9\}\quad B+7=\{3,7,8,10\}\quad B+8=\{4,8,9,11\}\] \[B+9=\{5,9,10,12\}\quad B+10=\{0,6,10,11\}\quad B+11=\{1,7,11,12\}\] \[B+12=\{0,2,8,12\}\]Assignment 4(32):

Let $B_1,B_2$ be two BIBD as follows and $B={c_{il},c_{js},c_{kt}}$, then:

\[B_1=\{a_0,a_1,a_2\}\] \[B_2=\{\{b_0,b_1,b_3\},\{b_1,b_2,b_4\},\{b_2,b_3,b_5\},\{b_3,b_4,b_6\},\{b_4,b_5,b_0\},\{b_5,b_6,b_1\},\{b_6,b_0,b_2\}\}\] \[\begin{matrix} & \begin{matrix} a_0 & a_1 & a_2 \end{matrix} \\ \begin{matrix} b_0 \\ b_1 \\ b_2 \\ b_3 \\ b_4 \\ b_5 \\ b_6 \end{matrix} & \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 & 2 \\ 3 & 4 & 5 \\ 6 & 7 & 8 \\ 9 & 10 & 11 \\ 12 & 13 & 14 \\ 15 & 16 & 17 \\ 18 & 19 & 20 \end{bmatrix} \end{matrix}\]$i=j=k$:

\[\{0,1,2\}\quad\{3,4,5\}\quad\{6,7,8\}\quad\{9,10,11\}\quad\{12,13,14\}\quad\{15,16,17\}\quad\{18,19,20\}\]$l=s=t$:

\[\{0,3,9\}\quad\{3,6,12\}\quad\{6,9,15\}\quad\{9,12,18\}\quad\{12,15,0\}\quad\{15,18,3\}\quad\{18,0,6\}\] \[\{1,4,10\}\quad\{4,7,13\}\quad\{7,10,16\}\quad\{10,13,19\}\quad\{13,16,1\}\quad\{16,19,4\}\quad\{19,1,7\}\] \[\{2,5,11\}\quad\{5,8,14\}\quad\{8,11,17\}\quad\{11,14,20\}\quad\{14,17,2\}\quad\{17,20,5\}\quad\{20,2,8\}\]$i\not=j\not=k$ and $l\not=s\not=t$:

In rows $0,1,3$:

\[\{0,4,11\},\{0,5,10\},\{1,3,11\},\{1,5,9\},\{2,3,10\},\{2,4,9\}\]In rows $1,2,4$:

\[\{3,7,14\},\{3,8,13\},\{4,6,14\},\{4,8,12\},\{5,6,13\},\{5,7,12\}\]In rows $2,3,5$:

\[\{6,10,17\},\{6,11,16\},\{7,9,17\},\{7,11,15\},\{8,9,16\},\{8,10,15\}\]In rows $3,4,6$:

\[\{9,13,20\},\{9,14,19\},\{10,12,20\},\{10,14,18\},\{11,12,19\},\{11,13,18\}\]In rows $4,5,0$:

\[\{12,16,2\},\{12,17,1\},\{13,15,2\},\{13,17,0\},\{14,15,1\},\{14,16,0\}\]In rows $5,6,1$:

\[\{15,19,5\},\{15,20,4\},\{16,18,5\},\{16,20,3\},\{17,18,4\},\{17,19,3\}\]In rows $6,0,2$:

\[\{18,1,8\},\{18,2,7\},\{19,0,8\},\{19,2,6\},\{20,0,7\},\{20,1,6\}\]Then we have construsted steiner triple systems above.

Assignment 5(52):

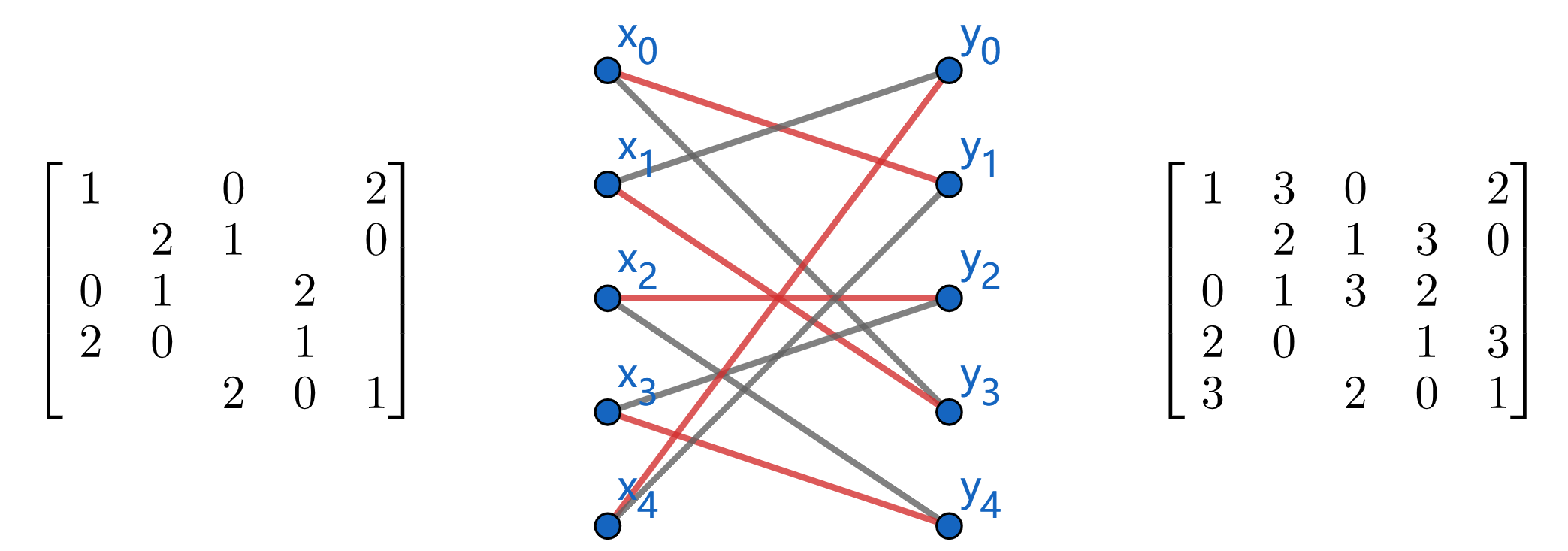

For rows $3$ and $4$, we can construct bigraph as follows to find one perfect matching to complete latin rectangle. Then add missing value to the last row.

Assignment 6(56):

For number $4$ and $5$, we can construct bigraph as follows to find one perfect matching to complete semi-latin square. Then add $6$ to the remaining spaces.

Polya counting

Permutation and Symmetry groups

Let $X$ be a finite set. Each permutation can be viewe as $f:X\mapsto X$ where $f(k)=i_k$. We can use a 2-by-n array to depict it:

\[\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 2 & \cdots & n \\ i_1 & i_2 & \cdots & i_n \end{pmatrix}\]- Composition: $(g\circ f)=g(f(k))$

- Associative law: $(f\circ g)\circ h=f\circ(g\circ h)$

- Identity permutation: $\forall k\in[1,n],l(k)=k$

- Inverse: $f^{-1}(k)=s\Leftrightarrow f(s)=k$, $f\circ f^{-1}=f^{-1}\circ f=l$

- Power: $f^k=f\circ f\circ\dots\circ f$

- $f\circ g=f\circ h\rightarrow g=h$

Denote $S_n$ as all $n!$ permutations of ${1,2,\dots,n}$. A permutation group is defined to be a non-empty subset $G$ of $S_n$, satisfying the following three properties:

- Closure under composition: $f\in G\wedge g\in G\rightarrow f\circ g\in G$

- Identity: $l\in G$

- Closure under inverses: $f\in G\rightarrow f^{-1}\in G$

$S_n$ is a special permutation group called the symmetric group of order $n$. $G={l}$ is also a permutation group.

e.g. 1: Consider a permutation $\rho_n$ as follows. Assume that the integers from $1$ to $n$ are evenly spaced around a circle. $\rho_n$ actually corresponds to a rotation of all integers. Specifically, $\rho_n^k$ is the rotation by $k\times2\pi/n$.

\[\rho_n=\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 2 & \cdots & n-1 & n \\ 2 & 3 & \cdots & n & 1 \end{pmatrix}\]All the permutations corresponding to all possible rotations form a permutation group $C_n={\rho_n^0=l,\rho,\rho^2,\dots,\rho^{n-1}}$ called cyclic group.

Let $Q$ be a geometrical figure. A symmetry of $Q$ is a motion (like rotation) that brings the figure onto itself. We can use permutation groups to depict these motions:

- $G_C$: corner-symmetry group

- $G_E$: edge-symmetry group

- $G_F$: face-symmetry group

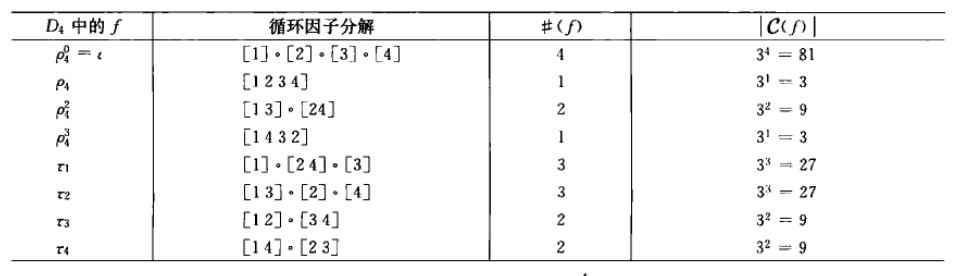

Consider a square with its corners labeled $1,2,3,4$ and edges labeled $a,b,c,d$. We have rotations and reflections acting on the corners to generate $G_C$. Denote $r_i$ as a reflection about $i$’s symmetry axis (always start at axis passing through $1$’s corner). We can get:

\[r_1=\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 \\ 1 & 4 & 3 & 2 \end{pmatrix}\qquad r_2\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 \\ 3 & 2 & 1 & 4 \end{pmatrix}\] \[r_3=\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 \\ 2 & 1 & 4 & 3 \end{pmatrix}\qquad r_4=\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 \\ 4 & 3 & 2 & 1 \end{pmatrix}\] \[G_C=\{\rho_4^0,\rho_4^1,\rho_4^2,\rho_4^3,r_1,r_2,r_3,r_4\}\]For all ($n\geq3$) regular n-gon, we can construct similar $G_C$, often called dihedral group of order $2n$.

Let $C$ be a collection of colorings of $X$ and $c\in C$ which represents color $c(1),c(2),\dots,c(n)$. Applying a permutation will change the position of original coloring:

\[f=\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 2 & \cdots & n \\ i_1 & i_2 & \cdots & i_n \end{pmatrix}\qquad c=\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 2 & \cdots & n \\ c(1) & c(2) & \cdots & c(n) \end{pmatrix}\] \[f(k)=i_k\Rightarrow c(k)=(f*c)(i_k)\] \[(f*c)(k)=c(f^{-1}(k))\] \[f*c=\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 2 & \cdots & n \\ f^{-1}(1) & f^{-1}(2) & \cdots & f^{-1}(n) \end{pmatrix}\]Notice for all $f\in G$, $fc\in C$. We call $c_1$ and $c_2$ are equivalent if there exists a $f$ such that $fc_1=c_2$.

Let $G(c)={f:f\in G,fc=c}$ which is called stabilizer working on fixed $c$ and $C(f)={c:c\in C,fc=c}$ working on stable $f$. Let $[c]$ be the orbit of $c$, that is, the equivalence class of $c$, then we have:

- $(g\circ f)c=g(f*c)$

- $fc=gc\iff f^{-1}\circ g\in G(c)$

lemma: $\vert G\vert=\vert[c]\vert\times\vert G(c)\vert$.

For $f,g\in G$, the equivalence class of $f$ is ${f\circ g:g\in G(C)}$, whose size is $\vert G(C)\vert$ corresponding to every $[c]$.

Burnside’s Theorem: Let $N(G,C)$ be the number of inequivalent coloring in $C$. Notice that each $[c]$ contribute $1$ to $N(G,C)$, then we have:

\[\sum_{f\in G}\vert C(f)\vert=\sum_{c\in C}\vert G(c)\vert=\sum_{c\in C}\frac{\vert G\vert}{\vert[c]\vert}=N(G,C)\times\vert G\vert\] \[N(G,C)=\frac{1}{\vert G\vert}\sum_{f\in G}\vert C(f)\vert\]e.g. 2: How many ways are there to arrange $n\geq3$ differently colored beads in a necklace?

$\vert G\vert=n+n=2n$. There is only one stable permutation $l$ corresponding to fixed colorings. Thus:

\[N(G,C)=\frac{1}{2n}(n!+0+0+\dots+0)=\frac{(n-1)!}{2}\]e.g. 3: How many inequivalent ways are there to color the corners of a regular 5-gon with the colors red and blue?

\[D_5=\{\rho^0,\dots,\rho^4,r_1,\dots,r_5\}\qquad\vert C\vert=2^5=32\] \[\vert C(\rho^k)\vert=\begin{cases} 32 & k=0 \\ 2 & k=1,2,3,4 \end{cases}\] \[\vert C(r_k)\vert=2^2\times2=8\] \[N(D_5,C)=\frac{1}{10}\times(32+2\times4+8\times5)=8\]e.g. 4: How many inequivalent ways are there to color the corners of a regular 5-gon with $p$ colors?

\[\vert C(\rho^k)\vert=\begin{cases} p^5 & k=0 \\ p & k=1,2,3,4 \end{cases}\] \[\vert C(r_k)\vert=p^2\times p=p^3\] \[N(D_5,C)=\frac{1}{10}(p^5+4p+5p^3)\]e.g. 5: $S={\infty\cdot r,\infty\cdot b,\infty\cdot g,\infty\cdot y}$. How many n-permutations of $S$ are there if we do not distinguish horizontal direction? (e.g. $rbgy==ygbr$)

\[f_1=\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 2 & \cdots & n \\ 1 & 2 & \cdots & n \end{pmatrix}\qquad f_2=\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 2 & \cdots & n \\ 1 & 2 & \cdots & n \end{pmatrix}\]Then the number of n-permutations on $S$ equals to $N(G,C)$ where $G={f_1,f_2}$ and $C={r,b,g,y}$. Thus:

\[\vert C(f_1)\vert=4^n\qquad\vert C(f_2)\vert=4^{\lfloor n+1/2\rfloor}\] \[N(G,C)=\frac{4^n+4^{\lfloor n+1/2\rfloor}}{2}\]Polya’s counting formula

Any permutation $f$ can be converted into cycle factorization as follows:

\[\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 6 \\ 6 & 4 & 5 & 2 & 1 & 3 \end{pmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 6 & 3 & 5 \end{bmatrix}\circ\begin{bmatrix} 2 & 4 \end{bmatrix}\]Let $#(f)$ be the number of cycles in the cycle factorization of $f$. Suppose we have $k$ colors to color elements in $X$, then:

\[\vert C(f)\vert=k^{\#(f)}\]e.g. 6: How many inequivalent ways are there to color the corners of a square with the colors red, white, and blue?

Let $e_i$ be the number of $i$’s cycle, and $z_i$ be the number of possible colors. Then we can use generating function to depict cycle index of $G$.

\[\#(f)=e_1+e_2+\dots+e_n\] \[P_G(z_1,z_2,\dots,z_n)=\frac{1}{\vert G\vert}\sum_{f\in G}z_1^{e_1}z_2^{e_2}\dots z_n^{e_n}\]e.g. 7: Determine the cycle index of $D_4$ (has shown in e.g. 6) and the number of ways to color a square with $k$ different colors.

\[P_{D_4}(z_1,z_2,z_3,z_4)=\frac{1}{8}(z_1^4+3z_2^2+2z_1^2z_2+2z_4)\] \[N(D_4,C)=P_{D_4}(k,k,k,k)=\frac{1}{8}(k^4+2k^3+3k^2+2k)\]e.g. 8: Let $p$ be a prime number. Determine the number of different necklaces that can be made from $p$ beads of $n$ different colors.

\[D_p=\{\rho^0,\dots,\rho^{p-1},r_1\dots,r_p\}\] \[P_{D_p}(z_1,\dots,z_p)=\frac{1}{2p}(z_1^{p}+pz_1z_2^{(p-1)/2}+(p-1)z_p)\] \[N(D_p,C)=\frac{1}{2p}(k^p+pk^{(p+1)/2}+(p-1)k)\]e.g. 9: Determine the number of each way to color a square with $2$ different colors.

\[P_{D_4}(r+b,r^2+b^2,r^3+b^3,r^4+b^4)=r^4+r^3b+2r^2b^2+rb^3+b^4\] \[N(D_4,C)=1+1+2+1+1=6\]e.g. 10: Determine the symmetry group of a cube and the number of inequivalent ways to color the corners and faces of a cube with a specified number of colors.

- (1) the identity rotation l (number is 1)

- (2) the rotations about the centers of the three pairs of opposite faces by

- (a) 90 degrees (number is 3)

- (b) 180 degree (number is 3)

- (c) 270 degree (number is 3)

- (3) the rotations by 180 degree about midpoints of opposite edges (number is 6)

- (4) the rotations about opposite corners by

- (a) 120 degrees (number is 4)

- (b) 240 degree (number is 4).

| symmetry | number | corner type | face type |

|---|---|---|---|

| $(1)$ | $1$ | $(8,0,0,0,0,0,0,0)$ | $(6,0,0,0,0,0)$ |

| $2(a)$ | $3$ | $(0,0,0,2,0,0,0,0)$ | $(2,0,0,1,0,0)$ |

| $2(b)$ | $3$ | $(0,4,0,0,0,0,0,0)$ | $(2,2,0,0,0,0)$ |

| $2(c)$ | $3$ | $(0,0,0,2,0,0,0,0)$ | $(2,0,0,1,0,0)$ |

| $3$ | $6$ | $(0,4,0,0,0,0,0,0)$ | $(0,3,0,0,0,0)$ |

| $4(a)$ | $4$ | $(2,0,2,0,0,0,0,0)$ | $(0,0,2,0,0,0)$ |

| $4(b)$ | $4$ | $(2,0,2,0,0,0,0,0)$ | $(0,0,2,0,0,0)$ |

Assignment 1(13-b,d):

\[f^{-1}*c(k)=c(f(k))\Rightarrow f^{-1}*c=(R,R,B,R,R,B)\] \[g\circ f=\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 6 \\ 1 & 2 & 5 & 3 & 4 & 6 \end{pmatrix}\qquad f\circ g=\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 6 \\ 2 & 5 & 3 & 4 & 1 & 6 \end{pmatrix}\] \[(g\circ f)*c=(R,B,R,R,B,R)\] \[(f\circ g)*c=(R,R,B,R,B,R)\]Assignment 2(20):

For a isosceles but not equilateral triangle, it has only two stable permutaions $\rho^0$ and $r_1$ corresponding to its axis of symmetry. Thus:

\[G=\{\rho^0,r_1\}\] \[\vert C(\rho^0)\vert=p^3\qquad\vert C(r_1)\vert=p^2\] \[N(G,C)=\frac{1}{2}(p^3+p^2)\]When using red and blue ($p=2$), there are $6$ coloring methods.

Assignment 3(26):

| $D_7$ | cycle factorization | monomial |

|---|---|---|

| $\rho^0$ | $[1]\circ[2]\circ[3]\circ[4]\circ[5]\circ[6]\circ[7]$ | $z_1^7$ |

| $\rho^1$ | $[1,2,3,4,5,6,7]$ | $z_7$ |

| $\rho^2$ | $[1,3,5,7,2,4,6]$ | $z_7$ |

| $\rho^3$ | $[1,4,7,3,6,2,5]$ | $z_7$ |

| $\rho^4$ | $[1,5,2,6,3,7,4]$ | $z_7$ |

| $\rho^5$ | $[1,6,4,2,7,5,3]$ | $z_7$ |

| $\rho^6$ | $[1,7,6,5,4,3,2]$ | $z_7$ |

| $r_1$ | $[1]\circ[2,7]\circ[3,6]\circ[4,5]$ | $z_1z_2^3$ |

| $r_2$ | $[2]\circ[1,3]\circ[4,7]\circ[5,6]$ | $z_1z_2^3$ |

| $r_3$ | $[3]\circ[2,4]\circ[1,5]\circ[6,7]$ | $z_1z_2^3$ |

| $r_4$ | $[4]\circ[3,5]\circ[2,6]\circ[1,7]$ | $z_1z_2^3$ |

| $r_5$ | $[5]\circ[4,6]\circ[3,7]\circ[1,2]$ | $z_1z_2^3$ |

| $r_6$ | $[6]\circ[5,7]\circ[1,4]\circ[2,3]$ | $z_1z_2^3$ |

| $r_7$ | $[7]\circ[1,6]\circ[2,5]\circ[3,4]$ | $z_1z_2^3$ |

Coefficient of $r^4b^3$: $\displaystyle\frac{1}{14}\times(\binom{7}{4}+7\binom{3}{2})=4$. Thus, the number of different necklaces containing $4$ red and $3$ blue beds is $4$.

Assignment 4(44):

| $D_4$ | cycle factorization | monomial |

|---|---|---|

| $\rho^0$ | $[1]\circ[2]\circ[3]\circ[4]$ | $z_1^4$ |

| $\rho^1$ | $[1,2,3,4]$ | $z_4$ |

| $\rho^2$ | $[1,3]\circ[2,4]$ | $z_2^2$ |

| $\rho^3$ | $[1,4,3,2]$ | $z_4$ |

| $r_1$ | $[1]\circ[3]\circ[2,4]$ | $z_1^2z_2$ |

| $r_2$ | $[2]\circ[4]\circ[1,3]$ | $z_1^2z_2$ |

| $r_3$ | $[1,2]\circ[3,4]$ | $z_2^2$ |

| $r_4$ | $[1,4]\circ[2,3]$ | $z_2^2$ |